In a recent note, Goldman Sachs summed up the changing nature of the industry in the context of copper this way:

“…fundamentals were once so connected to global growth, copper has been viewed as having a ‘PhD’ in macroeconomics.

“Yet today, ‘Dr. Copper’ no longer exists – with ESG, geopolitics and chronic underinvestment all driving copper fundamentals far more than overall global growth.

“In our view, Copper’s PhD is in public policy, not economics, rallying on concerns of Chilean mining royalties, accelerating European renewables demand and Russian sanctions supply risks rather than falling global growth expectations.”

Possible is the new probable

Resources may be measured or indicated, reserves may still be labelled proven and probable, but developing deposits has only become more uncertain.

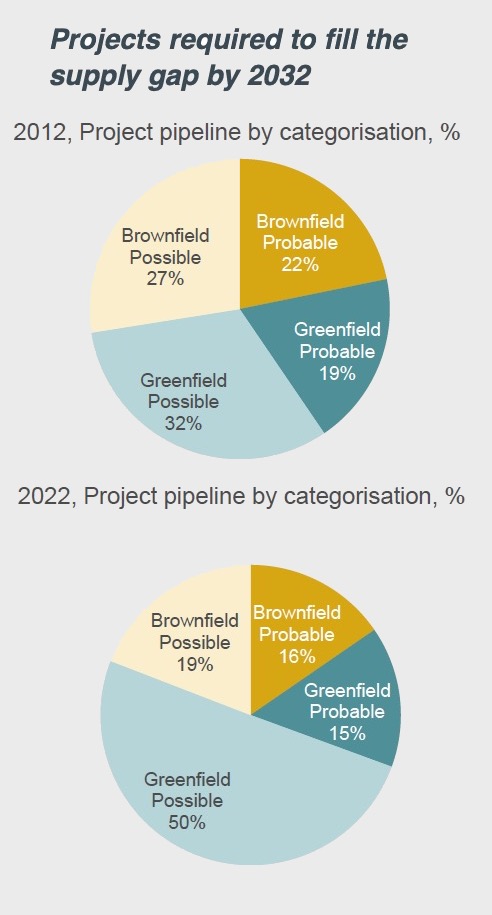

In a presentation at copper mining’s biggest annual gathering in Santiago, CRU head of base metal supply, Erik Heimlich, pointed out that while the size of the long-term supply gap of just over 6 million tonnes is in line with historical trends, filling that gap is a much more daunting prospect today.

Source: CRU

Source: CRU Foremost is the fact that now, remarkably, half the project pipeline for needed supply in 2032 consists of greenfield projects in the possible category; another 19% are speculative brownfield projects.

Comparing the 2022 project pipeline with that of 2012 makes for sobering reading. Of the 8 million tonnes per annum capacity identified as greenfield — possible projects 7 million tonnes remain undeveloped.

Heimlich says the preponderance of projects only rated as possible in the pipeline indicates the extent to which “factors beyond project economics are playing an increasingly significant role” in determining whether projects become mines.

How brown was your valley?

Only about a third of the 2012 uncommitted brownfield projects, which should be quicker, easier and cheaper to build, are in production or under construction now.

Notable 2012 projects that stayed so include Anglo American and Glencore’s $6.5 billion Collahuasi expansion, which was supposed to lift production at the Chile mine above 1m tonnes and BHP’s Olympic Dam project that started as “the mother of all digs” and ended up as an exercise in debottlenecking.

If new projects are more miss than hit, it’s up to mine life extensions, operational efficiency projects and mine restarts to make up the difference, but Heimlich cautions that while the “capital intensity of debottlenecking project may be attractive, additional tonnage is general low” and lack of scale can make these projects not worthwhile.

The success of mine restarts is also patchy, with few mines re-entering production and those that do generally small-scale.

Stopping stoping

Given the difficulty in bringing more projects online, mine life extensions “in this cycle appear to be more necessary than ever”, says Heimlich, but even these projects can fall foul of environmental, regulatory, community and political developments.

Anglo American has had to scale down its $3 billion Los Bronces project for environmental reasons, and will employ the sub-level stoping method in order to have no surface impact in an area with many glaciers, but doing so means significantly lower ore extraction than with block caving or open-pit operations.

And that may still not be enough for a green light – just this week Chile’s environment regulator denied the project an extension permit.

Tech tonic

Can technology plug the gap? Heimlich says new leach processes are “attracting significant interest and investment” and the total addressable market for low-grade sulphide leaching equals around 10 years of current output.

“New technologies provide the most significant upside to long-term production but could be beyond the requisite timeframe.”

Much like all those green, brown, possible, probable, committed and uncommitted projects that go beyond requisite timeframes.