Stable and abundant water supplies are becoming increasingly difficult to come by on a warming planet with a growing population. And according to new data, 37 countries in the world already face "extremely high" levels of water stress.

The Washington, DC environmental research organization World Resources Institute released the data from their Aqueduct project Thursday. Extremely high water stress means that more than 80 percent of the water available to the agricultural, domestic and industrial users in a country is being withdrawn annually and that the risk of water scarcity in a region is remarkably high.

"Water stress can have serious consequences for countries around the world," said Paul Reig, associate for WRI's Aqueduct project, to The Huffington Post. "Droughts, floods and competition for limited supplies can threaten national economies and energy production, and even jeopardize people’s lives. If countries and international-level decision makers understand more clearly where water stress is most severe, they can direct attention and money toward the most at-risk regions."

Researchers with the Aqueduct project looked at water risks in 100 river basins and 181 nations around the globe -- the first such country-level water assessment of its kind. By taking a close look at regional baseline water stress, flood and drought occurrence over several years time, inter-annual variability and seasonal variability as well as the amount of water available to a particular region every year from rivers, streams and shallow aquifers, WRI was able to give each country a score 0 to 5, with a 5 being the greatest level of water risk.

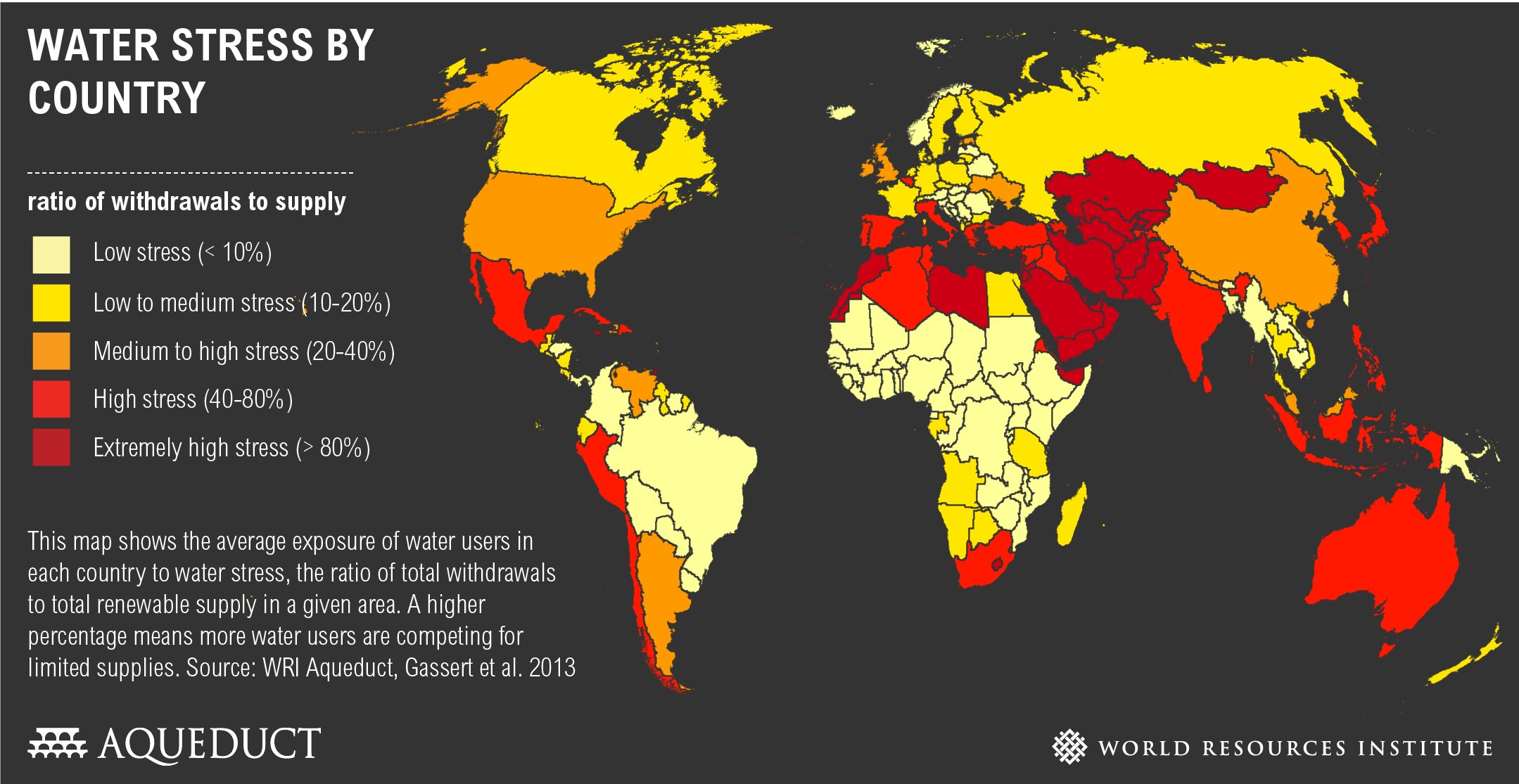

Baseline water stress is defined as the ratio of annual water withdrawals to total available annual renewable supply, a higher percentage, as illustrated in WRI's map, means more water users competing for increasingly limited water supplies:

WRI also produced a detailed interactive map using their recent data that can be found here.

WRI notes that it's important for a country to understand its risk of water scarcity and that extremely high levels of water stress doesn't mean that country will fall victim to water scarcity -- proper water management and conservation plans can help to secure a nation's water supplies.

"Publicly available rankings like these can help focus on regions facing the highest stress," Reig said. "International-level decision makers in agriculture, industry, and municipalities can use this information to identify regions with the highest need, then work together to improve water management and water security."

Take Singapore for example -- according to WRI, the country has the highest water stress ranking (5.0), a dense population and hasno freshwater lakes or aquifers, and its demand for water far exceeds its naturally occurring supply.

But Singapore is an exceptional water manager, WRI points out in its blog, and is able to meet its freshwater needs:

Advanced rainwater capture systems contribute 20 percent of Singapore’s water supply, 40 percent is imported from Malaysia, grey water reuse adds 30 percent, and desalination produces the remaining 10 percent of the supply to meet the country’s total demand. These forward-thinking and innovative management plans provide a stable water supply for Singapore’s industrial, agricultural, and domestic users—even in the face of significant baseline water stress.