Following what was a mostly quiet holiday weekend for trade-war-related rhetoric (other than a dollop of trade-deal optimism offer by President Trump, little was said by either side), Beijing has started the holiday-shortened week by reiterating threats to embrace what we have described as a 'nuclear' option: restricting exports of rare earth metals to the US.

Global Times editor Hu Xijin, who has emerged as one of the most influential Communist Party mouthpieces since President Trump increased tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese goods, tweeted that China is "seriously considering restricting rare earths exports to the US."

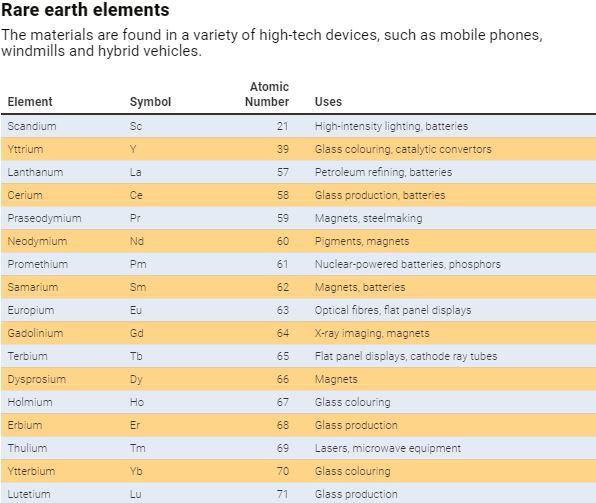

There are signs that these warnings should be taken seriously: One week ago, President Xi and Vice Premier Liu He, China's top trade negotiator, visited a rare earth metals mine in Jiangxi province. Rare earths, which are vital for the manufacture of everything from microchips to batteries, to LED displays to night-vision goggles, have been excluded from US tariffs.

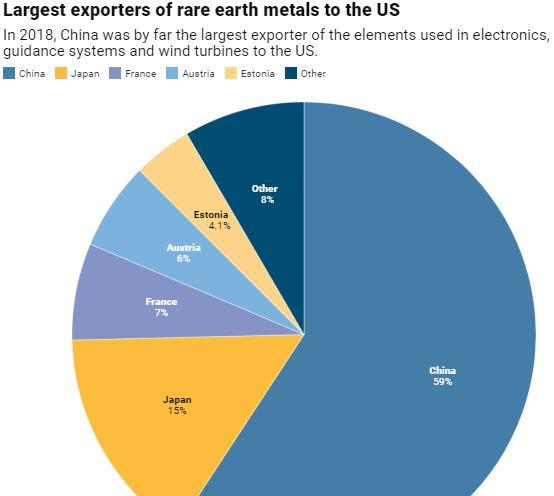

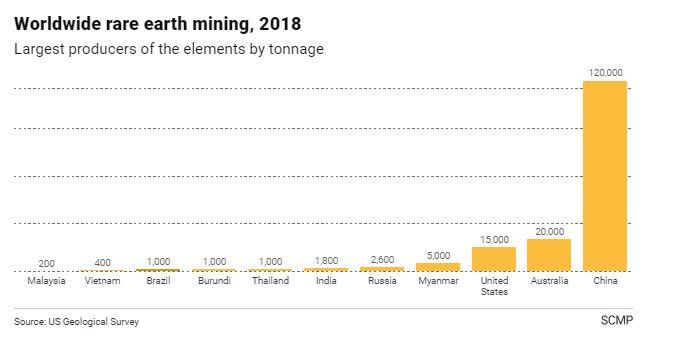

Though other Chinese officials have denied that export curbs were being considered, Xi's visit was widely viewed as a symbolic warning. Seven out of every 10 tons of rare earth metals mined last year were produced by Chinese mines. One analyst warned that Xi's visit was intended to send "a strong message" to the US.

Beijing is limited in its ability to retaliate against Washington's tariffs by the fact that there simply aren't enough American-made goods flowing into the Chinese market. Because of these limits, it's widely suspected that Beijing will find other ways to retaliate. Though they are more plentiful than precious metals like gold and platinum, rare earths can be expensive to refine and extract.

The tension has sparked a 30% increase in 'heavy rare earth' metals.

The prices of so-called heavy rare earths, which are used in batteries for electric vehicles and in defence applications, have risen 30 per cent this year, said Helen Lau, senior analyst and head of metals and mining research at Argonaut in Hong Kong.

"I think it is a little bit reckless, from my point of view, for China to ban the export of rare earths to the US directly," Lau said. "There’s always some way to have a similar impact...Maybe we want to reduce exports to everyone. That is a likely scenario."

Even if Beijing doesn't follow through on these threats, some analysts suspect that, given their scarce supply, China might move to restrict their export to help meet domestic demand. Beijing has already slapped tariffs on rare earths mined in the US.

Lau said she believes China, regardless of the trade war, will ultimately move to reduce exports of rare earths to meet its own domestic demand.

"Everyone knows that China needs rare earths for its electric-vehicle industry," Lau said. "Electric-vehicle production is very strong – every single month it is growing in high double digits, and this year it has doubled from last year. The demand for rare earths is very strong."

According to the SCMP, June could be a critical make-or-break moment for the global rare earth metals trade, because that's when China is expected to set its mining quota for the second half of the year. The quota for the first half of the year was 60,000 tonnes, unchanged from the year prior.

There is precedent for a rare earth export ban: China briefly limited exports of rare earth materials to Japan back in 2010 after a Chinese trawler collided with Japanese patrol boats near a disputed island. Beijing also briefly imposed licenses, quotas and taxes on rare earth elements but removed many of them in 2014 after the US and Japan complained to the WTO.

To wean the US off its dependence on Beijing, one American chemicals company on Monday signed an MoU with an Australian mining firm to develop a rare earths mine in Hondo, Texas to help compensate for the "critical supply chain gap." And Japanese scientists recently announced the discovery of a massive cache of rare earths on the sea floor off the coast of Tokyo.

But whether these alternatives can be cultivated in time is very much in doubt. Still, Beijing is likely wary of resorting to an export ban since it would likely only work once. Once the option has been invoked once, analysts say, efforts to develop these alternative sources will likely accelerate.