After years of buying at the peak of the economic cycle and selling in the trough, could the world’s big diggers do the reverse? Compared to peers in oil and gas, Rio Tinto Group and the largest diversified miners are riding out the coronavirus storm in sheltered positions: They have low operating costs, little debt and more than $60 billion in liquidity.

History matters here. Just over a decade ago, miners binged on hubristic investments like Rio’s acquisition of aluminum producer Alcan or Anglo American Plc’s Minas Rio iron-ore venture. In the hangover years between 2012 and 2016, some $200 billion was written off, and a generation of chief executives were shown the door. It was a near-death experience akin to what the energy sector is going through today, and one that left behind an industry focused on cleaning up, cutting back and returning cash to shareholders. Rio has been among the most generous, handing back $36 billion since 2016.

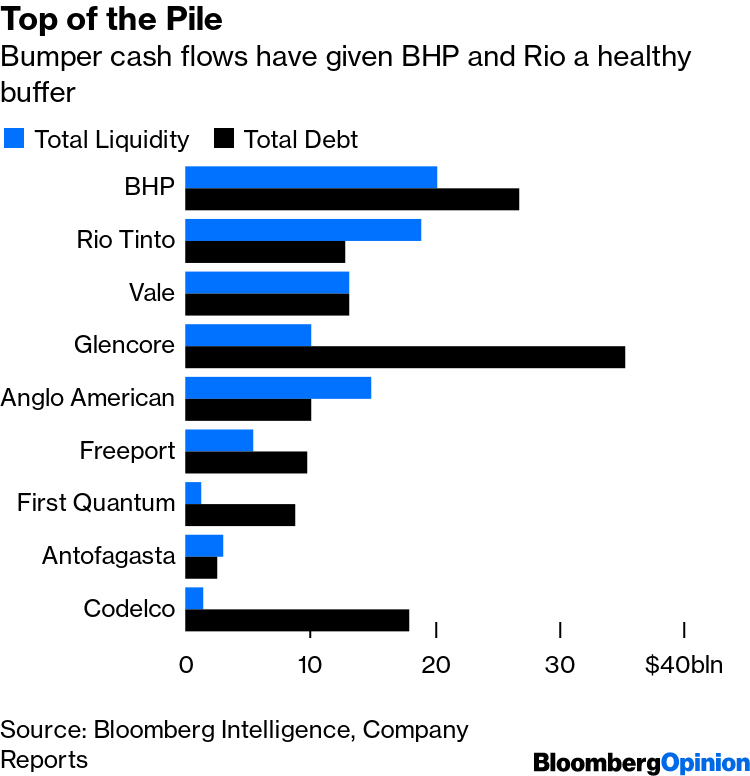

It means the industry’s largest players went into this crisis with two things: balance sheets at their most robust in years, and a pedestrian growth outlook. Almost the opposite is true at long-coveted targets like Freeport-McMoRan Inc., with a market value of $11 billion, and First Quantum Minerals Ltd., valued at $3.5 billion. These mid-size base metal producers are beginning to look fragile, with expanding copper mines but nearly $19 billion of total debt between them. Their shares have fallen more than 40% this year. No one knows how long a recovery from the pandemic will take, or what life will look like on the other side, but miners have a little more certainty than most: Metals like copper, used for electrification and a host of consumer goods, will be needed, and will be in short supply. It’s a tantalizing state of affairs.

As ever, things aren’t quite that simple, and even the heftiest miners aren’t immune to the world’s turmoil. BHP Group has to contend with the crashing oil price. Anglo American is dealing with lockdowns in South Africa, Peru and elsewhere, as governments try to contain the spread of coronavirus. Glencore Plc, long the most buccaneering of the large players, is tackling succession, trouble in Zambia and a pending U.S. Department of Justice investigation into its business practices.

At Rio, Chief Executive Officer Jean-Sebastien Jacques has perhaps the strongest motivation to act. He is less exposed to many of these uncertainties, and is running a miner that still relies on iron ore for about three-quarters of its Ebitda, as steel consumption hovers at or near a peak in China. Large mainland miners, like acquisitive Zijin Mining Group or Jiangxi Copper Co., may be his competitors. There are cashed-up bullion players, too: Barrick Gold Corp.’s CEO, Mark Bristow, has said he could consider copper and even Freeport’s Indonesian Grasberg mine.

The trouble is, we’re not yet at the distress levels that will prompt boards to approve a rush for checkbooks. Travel and due diligence are impossible, markets are too volatile for share deals and the next few months remain an unknown quantity. Shareholders may balk. In past crises, even distressed sellers were able to command premiums, so bargains will be tough. Copper prices are still above the depths of 2016.

Worse, not even the most obvious prey would be easy to snap up: Freeport and First Quantum come with traps. Freeport, the world’s largest listed copper producer, faces the question of who will lead it when veteran Richard Adkerson retires, along with concerns over older U.S. mines and the costly move underground at Grasberg. Rio, unhappy with the environmental and political risks, sold its interest in the Indonesian mine in 2018. First Quantum, more bite-sized and so perhaps more appealing, battened down the hatches earlier this year with a poison pill, after Jiangxi Copper built an 18% stake. Its flagship Cobre Panama mine has yet to operate through a full wet season. Chinese players eyeing miners with Australian assets, meanwhile, would also have to deal with a regulator bent on discouraging opportunistic foreign bargain-hunters.

Yet the longer the pandemic lockdowns drag on, the more the pain increases, as fixed costs go out and no cash comes in. It’s visible already in lithium, with Tianqi Lithium Corp. seeking to sell part of its stake in the Greenbushes operation in Australia, as it struggles to repay debt taken on to buy a stake in Chilean giant SQM. It’s rare to see large Chinese producers in distressed sales, even if lithium prices have plummeted since 2018. Rare-earth producer Lynas Corp., meanwhile, says it may need public funds to complete an ore-processing plant.

Buyers won’t pounce yet. A global economic recovery isn’t in sight and will be slow; most will need a little more confidence that growth is coming back. That will mean a wider improvement than China’s stimulus and return to work, as encouraging as State Grid Corp.’s 2020 investment plans may be. They’ll also need travel restrictions to lift. Wait too long, though, and the opportunity to buy cheap will pass — again.