What you’ll learn in this article

- What is China’s new central bank digital currency, and how it could affect the U.S.

- How the e-RMB compares with other Chinese mobile payment systems, like Alipay

- How CBDCs work, and why governments are clamoring for them

- What a cashless society would look like, and concerns about privacy

After years of rumors and speculation, China’s digital renminbi has officially rolled out in parts of China for pilot tests. But in a country that already does not use much cash and where mobile payments through the likes of Alipay and WeChat Pay are already ubiquitous, how much will an e-RMB really matter to the average Chinese person, the laobaixing?

Cities taking part in the pilot include Shenzhen, Suzhou, Xiong’an New Area and Chengdu, where people with accounts at major state-owned banks such as the Agricultural Bank of China can create a Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP) wallet in their bank’s mobile app.

In what has been the most official announcement to date, China’s Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily recently published a story introducing the DCEP system, stating that the app’s functions also include digital currency exchange, wallet management and transaction records as well as basic payment receiving and collecting.

While the DCEP trials are going on, People’s Bank of China (PBOC) governor Yi Gang has been downplaying their significance. “[The tests] don’t mean the official launch of a digital yuan… there’s no timetable for an official launch,” said Yi in a recent interview with the central bank’s publication China Finance.

Along with being able to use the DCEP to pay for goods and services at such businesses as Starbucks and McDonald’s, the pilot makes reference to the 2020 Winter Olympic Games in Beijing. “That implies that it will take well more than a year before the PBOC fully launches its digital currency,” said Zhiguo He, a professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, in an article he wrote for Forkast.News.

But China’s DCEP — the world’s first central bank digital currency (CBDC) for a major country — is already setting off global worries for its future potential to challenge the U.S. dollar in primacy. Once it is nationwide, the digital RMB could also become a valuable instrument for the Chinese government for monetary policy as well as tracking money.

What do the people of the People’s Republic think of this new official digital currency? To find out, Forkast.News talked to a variety of Chinese citizens in different parts of the country.

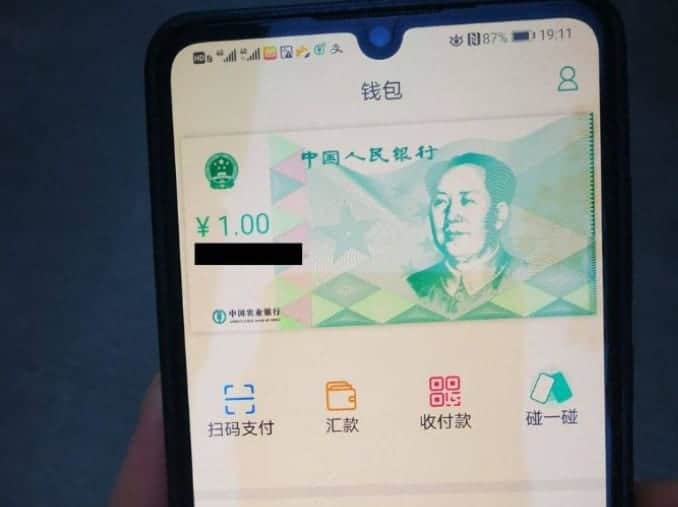

Am alleged screenshot of China’s digital currency app has revealed functions similar to mobile payment apps. Image: Chainnews.com

Am alleged screenshot of China’s digital currency app has revealed functions similar to mobile payment apps. Image: Chainnews.com “[The DCEP] will further enhance the current cashless society while maintaining the status of cash in a cryptocurrency format,” said Lim Wei Ming, resident manager at the Shangri-La hotel chain in Shenzhen.

A content manager at one of China’s largest internet companies said she is already accustomed to making payments by WeChat Pay, so she likely will not change that habit.

“But it depends on how DCEP will promote itself in the future,” said Zhang Fan, who lives in Beijing and declined to identify her employer.

See related article: What is China’s new CBDC, and what is it not?

Big difference over mobile payment?

The DCEP will function both as legal tender and electronic payment. Like physical cash and unlike debit cards or a private digital pay system like Apple Pay, eventually retailers will not be allowed to refuse it. Although China’s DCEP does not incorporate the decentralization aspects of blockchain technology, it does make use of smart contracts, cryptography and tracking to enhance anti-money laundering efforts and tax evasion.

Because it would be state issued and controlled, central bank digital currencies (CBDC) like the DCEP would respond much more to monetary policies than credit cards or cryptocurrencies like bitcoin that are independent of the government. The digitization of cash can also help governments keep tighter control over money in circulation, known as M0, which otherwise are harder for central banks to track.

Economists say the DCEP would additionally give the PBOC, China’s central bank, greater ability to change interest rates to spur consumption. Increased consumption is one of China’s goals set out in its 13th Five Year Plan, which lays out long term economic strategies up to 2020.

But in China, where mobile payments through popular applications like Tencent’s WeChat Pay and Alibaba’s Alipay are already in wide use, where would the DCEP fit into the average person’s financial ecosystem?

DCEP offers features that current digital payment systems don’t have, such as “double off-line transactions,” which allows users to transfer and receive the e-RMB directly to and from each other without having to go through the internet or mobile networks.

“There is a small chance that Tencent or Alipay may fail the next day, which also favors the DCEP a bit,” He, the Chicago Booth professor, told Forkast.News. But he added that such a scenario — involving corporate behemoths that have been described as the Amazon and Facebook of China — is unlikely.

According to the PBOC, China is leapfrogging over credit card technology, with mobile payments reaching 277.4 trillion yuan (US$39.07 trillion) in 2018 — more than 28 times what it was in 2014. Economists say that the DCEP, aside from its impact on China’s domestic monetary policy, could also one day start to replace the U.S. dollar in cross-border transactions and international finance if it becomes widely accepted by China’s trading partners.

An Alipay user pays for a service by scanning a QR code through the app. Image: Alibaba Group

An Alipay user pays for a service by scanning a QR code through the app. Image: Alibaba Group Still, the DCEP may not make much of a difference to most people. “Although there is little change from the user’s perspective, from the perspective of central bank supervision, future forms of finance, payment, business and social governance etc, this is the biggest thing ever,” Xu Yuan, associate professor at Peking University’s national development research institute told Chinese state broadcaster CCTV.

“What is the incentive not to use [the DCEP]? It is a fun technology,” said He, the University of Chicago Booth professor. “Digital transactions have got in every individual’s daily life and it is quite natural to have people start using it, as long as they have bank apps.”

Cashless payments are already so commonplace in China that users only need to use their mobile phone to scan a QR code at points of sale. From there, the transaction is then automatically digitally processed through apps like WeChat Pay and Alipay that are linked to users’ bank accounts.

Cash is so rarely used that even street beggars in China have reportedly set up printed QR codes to receive handouts from passersby. Credit cards have also fallen out of favor because they require stores to set up credit card-processing infrastructure that is onerous to use and charges high fees for transactions.

“In China, [being] cashless has been a way of life after Alipay and WeChat Pay toppled the use of cash and credit cards,” said Lim, the hotel manager. “Chinese people will endorse and not detest [the DCEP].”

According to a 2018 report from the China Internet Network Information Center, there are over 500 million Chinese people who use their mobile phones to make payments. Now, that number is likely even higher.

Video game store owner Da Lin hasn’t used any cash at his Shenzhen store, located in a busy electronics shopping district, for the past three years. “For businesses like ours, I actually want no cash because it is simpler,” he told Forkast.News. “Now almost no one goes out with cash.”

As for China’s new digital currency, Lin’s reaction is essentially a shrug.

“[The DCEP] doesn’t matter for us for better or worse… because now WeChat, Alipay or other payment methods have basically covered all aspects of our lives, ” Lin said. “If the payment method is the same, the digital renminbi is just one more payment method.”

But some people still have misgivings about the possibility of an entirely cashless world.

“If I store my money in banks, I can withdraw cash from the banks, but if every cash becomes electronic, it would be very easy for someone to steal them electronically, right?” said Mary Zheng, a Chinese literature teacher in Guangzhou.

People also wondered about DCEP’s impact on big data. The DCEP could be like a one-way mirror, making the lives of ordinary users more transparent and easier to exploit by the government and companies with access to that data, but ordinary people will not be able to see what they are doing, said Grace Li, a mainland student majoring in finance and economy at the University of Hong Kong.