Canada’s natural gas producers will face the greatest burden among energy companies under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s new emissions-reduction plan, just as the industry faces renewed pressure to increase output.

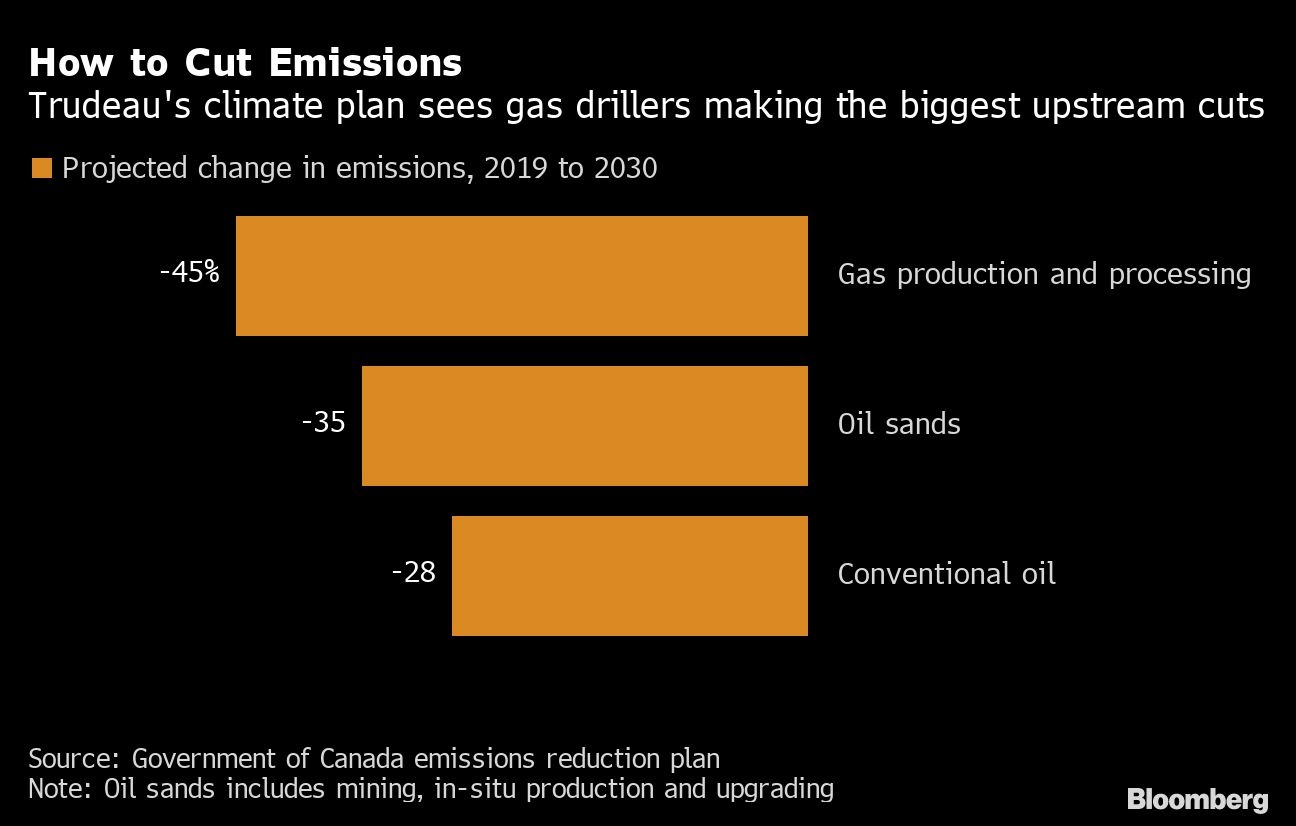

Gas drillers and processors are projected to cut emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 versus 2019 levels. That compares with a 35 per cent reduction that’s expected from larger-emitting oil sands producers, according to government documents. Dozens of companies operate gas wells, pipelines and processing plants scattered across the country, often in remote regions, making it challenging to deploy technologies that control carbon.

Trudeau’s climate plan comes as Canada faces demands to increase its gas output. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has focused attention on finding alternative supplies for Europe, giving impetus to long-delayed projects to ship Canadian liquefied natural gas abroad.

“I think we are kind of on a tightrope,” said Mark Oberstoetter, lead analyst for upstream research at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. in Calgary. “We want to be ambitious with these targets but also fill LNG Canada,” a huge LNG facility backed by Shell Plc that’s being built on the west coast.

The multitude of gas producers don’t have a single goal. For example, the government plan calls for a 42 per cent total reduction in emissions from the oil and gas sector. Oil sands companies have set a 32 per cent target through a plan called Oil Sands Pathways to Net Zero.

“Those are ambitious numbers, there is no question,” said Tristan Goodman, chief executive officer of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, a trade group representing gas explorers.

METHANE PROBLEMS

Much of the target will have to be met through methane reduction and by switching to low- or zero-emitting electricity for running wells and other machinery, such as hydroelectricity from British Columbia, Goodman said.

Methane often leaks out from valves and other openings in the network of gas wells, pipelines and processing plants that crisscross the country. The government has set a specific 75 per cent target for methane cuts by 2030 compared with 2012 levels. Sealing those leaks is a process that is already well underway, making it a “low-hanging fruit” for the industry, Oberstoetter said.

Tourmaline Oil Corp., one of Canada’s largest gas producers, achieved a net 25 per cent methane reduction target last year, three years earlier than anticipated, Michael Rose, its chief executive officer, said in an earnings call in March. Crescent Point Energy Corp., a conventional oil and gas producer, is aiming for a 75 per cent reduction in methane emissions by 2025.

Carbon capture and storage may become an option for meeting the goal, but policies such as Alberta’s plan to create massive hubs for storing carbon may not be attractive to some gas producers that want to store carbon in their own pour spaces, closer to the source, Goodman said.

Gas production in Canada was forecast to remain mostly flat through most of the next decade if policies to cut emissions continue to tighten, according to a report by the Canada Energy Regulator in December. The climate plan released this week forecasts that gas output could fall 13 per cent by 2030. But the Ukraine war has sent European countries racing to find alternative supplies to replace Russian gas.

Canada is now in discussions with European partners about the prospect of supplying them with LNG. While just one project is under construction, another company called Woodfibre LNG has said it plans to spend US$500 million ($625 million) this year on its US$1.6 billion project off British Columbia. A handful of LNG projects in Eastern Canada are also being planned, including one off Newfoundland that has generated European interest, according to the company behind the the project.

The biggest risk for the government is that the industry deems its climate plan is too ambitious, compelling them to leave Canada, Goodman said.

“What we are always trying to balance,” Goodman said, “is the desire and willingness to reduce those greenhouse gas emissions but, at the same time, you don’t want to have production shifting into other jurisdictions” with more lax climate policies.