Shell's and TotalEnergies' Graff and Venus deepwater discoveries off Namibia have put southern Africa under the exploration spotlight. With deepwater offering high productivity reserves, it's a spotlight that's likely to linger for a few years yet, despite continued offshore upstream capital discipline.

With talk of TotalEnergies' offshore Namibia Venus discovery potentially containing more than 11 billion boe in place, and recoverable resources estimated at 3 billion, it's a major find. If developed, it would set a new record as the world's deepest water development.

It's not alone. The Venus discovery comes hot on the heels of a string of other large discoveries in southern Africa; Shell's nearby Graff discovery, on adjacent acreage just southeast of Venus; and Brulpadda and Luiperd, also discovered by TotalEnergies, off neighboring South Africa. Combined, these discoveries help cement southern Africa's position in the international exploration limelight.

Dr. Andrew Latham, Wood Mackenzie's Vice President, Energy Research, expects these finds to make the region "a hot spot for drilling in 2023 and 2024 and beyond, with "running room" within Namibia and South Africa, it won’t necessarily be a frenzy but there will be a lot more wells."

For Impact Oil and Gas, which has a 20% stake in Venus, it's big news. In Philip Birch, Impact's Exploration Director's words: "This play-opening discovery firmly places the deepwater Orange Basin as one of the world's most exciting areas for hydrocarbon exploration."

All eyes on Namibia

It's been a long time coming for this Atlantic coast country, which shares borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east, and South Africa to the south and east.

Namibia's offshore basins – stretching along its 1,600 km coastline – comprise the Orange River Basin in the south and the Luderitz and South Walvis Basins to the north, all formed during the late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous following processes that resulted in a north-south rift system along today's southwest African margin – although of course it's a little more complex than that.

Until the early 2010s, most of the few wells that had been drilled were in relatively shallow waters on the shelf. While the Kudu gas field was discovered in 1974, a lack of route to market has seen it left fallow, despite going through the hands of multiple operators. However, drilling in the early 2010s moved into deeper waters, where there were more promising signs. While no commercial discovery was made, the Wingat discovery in the Walvis Basin by Brazil's HRT in 2013, and a handful of other wells, proved Aptian source rock in the basin.

Meanwhile, "There's been a general learning that you could go further offshore and that reservoir and that the source might be better than imagined a few years ago," says Latham. "On the technology side, there's also a growing confidence that 3,000 meters water depth isn't the technology hurdle it might have been."

Deepwater drilling

So, fast forward to 2021, and both Shell and TotalEnergies had started to spin bits off the Namibian shelf; Shell at Graff using the Valaris DS-10 drillship and TotalEnergies at Venus, using Maersk Drilling's Maersk Voyager drillship.

Shell struck success first, with the Graff discovery in 2,000 meters water depth, 270 km offshore, announced by partners QatarEnergy and National Petroleum Corporation of Namibia (NAMCOR) in February. Just weeks later, TotalEnergies' discovery Venus, ~325 km offshore in 3,000 meters water depth in block 2913B, was announced. QatarEnergy and NAMCOR are also partners, as well as Impact Oil and Gas.

Graff is thought to contain 5 billion boe in place, with Wood Mackenzie carrying close to 2 billion as an estimate for recoverable volumes. That could change once there has been a well test on the field, says Latham. For Venus, Wood Mackenzie is carrying a 3 billion barrel estimate. But, "It’s potentially much bigger than that,” says Latham, with a slightly different age reservoir, which would suggest a better liquid to gas ratio than Graff.

Fast track developments

Graff has already been highlighted by the Namibian government as a potential fast-track development. This would likely be through a phased development, following a similar philosophy to ExxonMobil’s Liza field development offshore Guyana, which came onstream within five years and will see additional FPSOs added over the years.

A similar approach is expected for Venus, with the caveat that the water depth at Venus is 3,000 meters, nearly double compared to the recently launched Liza Unity FPSO, the second FPSO at Exxon’s Stabroek Block offshore Guyana, which is moored in water depth of around about 1,650 meters.

If developed, Venus would top Shell’s Stones field in the US Gulf of Mexico as the world’s deepest water development, where the FPSO is moored in 2895.6 meters water depth.

Wood Mackenzie has suggested first oil could flow from Venus by 2028, via 35+ production wells tied back to a leased FPSO.

“You’re probably looking at 900 million barrels in an initial project,” says Latham. “A phased development makes a lot of the decision making easier.”

However, TotalEnergies will also have to find an offtake solution for the gas content in the Venus reservoir. Initially, that’s likely to mean recycling and reinjection, in order to not delay liquids production. Longer-term, it means finding a market for the gas, which would point to a multi-Tcf LNG export project.

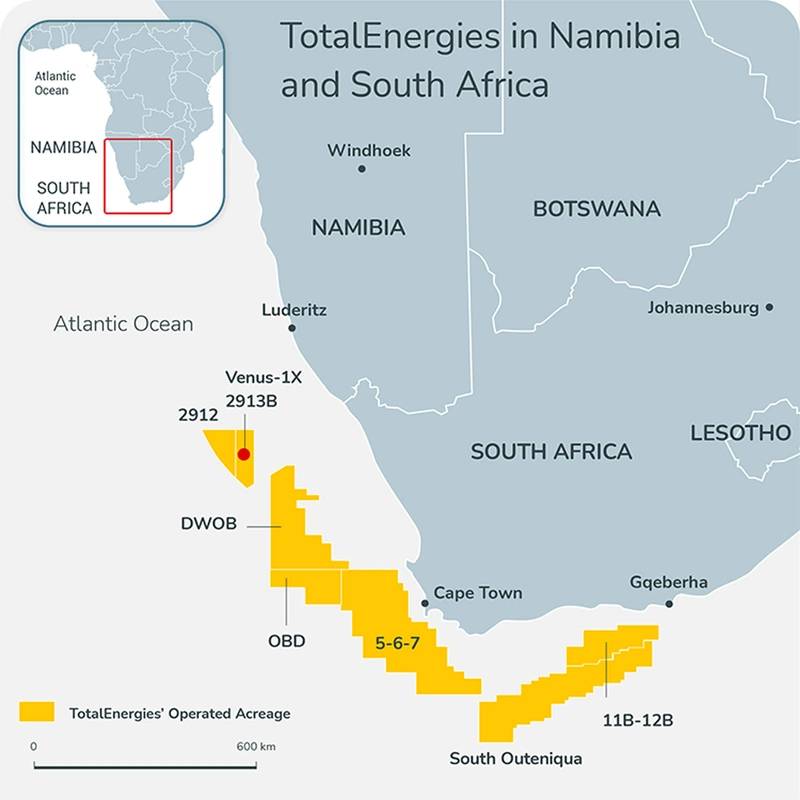

Venus Map. Image courtesy TotalEnergies

Venus Map. Image courtesy TotalEnergies

Time for appraisal

Shell has already started appraisal work on Graff, with the La Rona well, while TotalEnergies is planning its appraisal of Venus later this year. Outside of these two discoveries, Latham thinks there’s plenty of running room yet for Namibia, with Shell already looking at further exploration close to Venus on its acreage later this year. But there’s also running room elsewhere, he says. “There are other places on the African margin that might have good running room based on the same drilling densities,” says Latham. “Southern Angola, for example, barely drilled. ExxonMobil took a big acreage footprint two-three years ago. They said at the time it’s very frontier, but there are enough clues to make it interesting, and if it works it could be on the scale of Guyana and there are other places where similar stories are possible.”

Success offshore Namibia could also help spur activity in South Africa. “It’s only a matter of time before we see Shell and TotalEnergies coming into the Orange Basin alongside Venus and Graff, but within South Africa,” says Latham. “They have a big acreage footprint that side of the border.”

But, he adds, progress has been slow in South Africa, with securing permits for operations such as shooting seismic proving fraught at times. While South Africa has long had a small offshore industry, it’s on a bit of a new territory for governance and regulation, he says.

These challenges have resulted in some operators passing over licenses. The two headline discoveries, Brulpadda and Luiperd (Leopard), also contain a lot of gas, and that will need to find a domestic market “and that’s not going to be super quick to do that, when you look at the broader south African power market,” says Latham.

Deepwater in a continuing capital discipline environment

Offshore upstream spending still hasn’t returned to pre-Covid levels, despite a price environment that’s “changed out of all recognition.”

“The overall context is (still) capital discipline,” says Latham. But increasing reservoir quality in deepwater is making projects like the Stabroek discoveries and Graff and Venus attractive, thanks to higher productivity, measured by reserves produced per well.

“A lot of new deepwater development wells, such as in Guyana or the Santos Basin [offshore Brazil], are seeing 20-30 million barrels per well, which is extremely commercial,” says Latham. “Some of the earlier deepwater plays, like the Gulf of Mexico and Angola, it’s probably only half of that. So big the exploration successes in recent years have brought the industry into even more productive deepwater reservoirs than they already had.”

This is true for oil, but also gas, he says, with fields like Zohr [in Egypt] proving highly productive. The Israeli deepwater and Cypriot wells, if developed, are expected to be very highly productive, with Tcf levels per well. In these cases, “The commerciality isn’t burdened by the cost of drilling the well,” says Latham. “If we are getting 20 or 30 million barrels out of a well, even if that well is costing you $50 million, or even $100 million, it’s only adding a few dollars per barrel to the capital cost.”

Part of the reason for this trend in increasing productivity is operators being pickier about what they pursue.

“We might have $100 oil at the moment, and our long-term Brent forecast is $80/b, but of companies are using $60/b as a planning assumption and $40 or even $30 as a breakeven for big new developments. If you use a low breakeven hurdle, you really have to have a high-quality reservoir and that’s forcing them into good quality deepwater plays.”