Viruses Nearly three dozen people in China have been sickened by a newly identified virus.”

Nope, that isn’t a throwback to 2020. Scientists have identified a new virus named Langya henipavirus, or LayV. The good news is that we’re talking about just 35 cases since 2018, and it doesn’t look like human-to-human transmission is possible (shrews are thought to be natural carriers of the virus).

It’s thanks to an early warning system that we know about this virus, but that doesn’t mean we can relax. LayV is just another example of zoonotic spillover, where pathogens jump between animals and humans. Around 60% to 75% of our infectious diseases are derived from pathogens that started off circulating in another part of the animal kingdom. If there’s a new pandemic, you can bet it’ll be a zoonotic disease.

The problem is that zoonotic spillover is happening more frequently. Andreas Kluth has called it one of the greatest dangers to humanity. As the planet warms, and humans encroach further and further into wildlife habitats, animals — including ourselves — will come into close contact with species new to them. That gives pathogens an incredible opportunity to mingle and evolve and eventually make the jump to humans. One recent paper can give us a number: In the most conservative warming scenario, another 15,000 viruses will hop among 3,000 mammal species by 2070. Things are already accelerating, as this dataset of the top 100 zoonotic outbreaks and 200 randomly chosen outbreaks show:

Several other zoonotic diseases have been making headlines, including monkeypox and, of course, Covid-19. But another disease — one that did not originate in animals — can provide lessons in how to mitigate such threats as well as a wake-up call.

The battle against polio is one of the world’s greatest public-health successes. After a global initiative to eradicate the disease began in 1988, it was left endemic in just two countries — Afghanistan and Pakistan — and there were hopes we could get rid of it for good. But now it’s threatening to make a comeback: In July, the US reported its first polio case in nearly a decade; a girl in Israel developed paralysis in March; and poliovirus has been found in London sewage, prompting the offering of a polio booster to all children under the age of 10 in the city.

It’s concerning, especially when a health official in New York state has warned that there could be hundreds of undiagnosed polio cases, highlighting the importance of building trust around vaccinations.

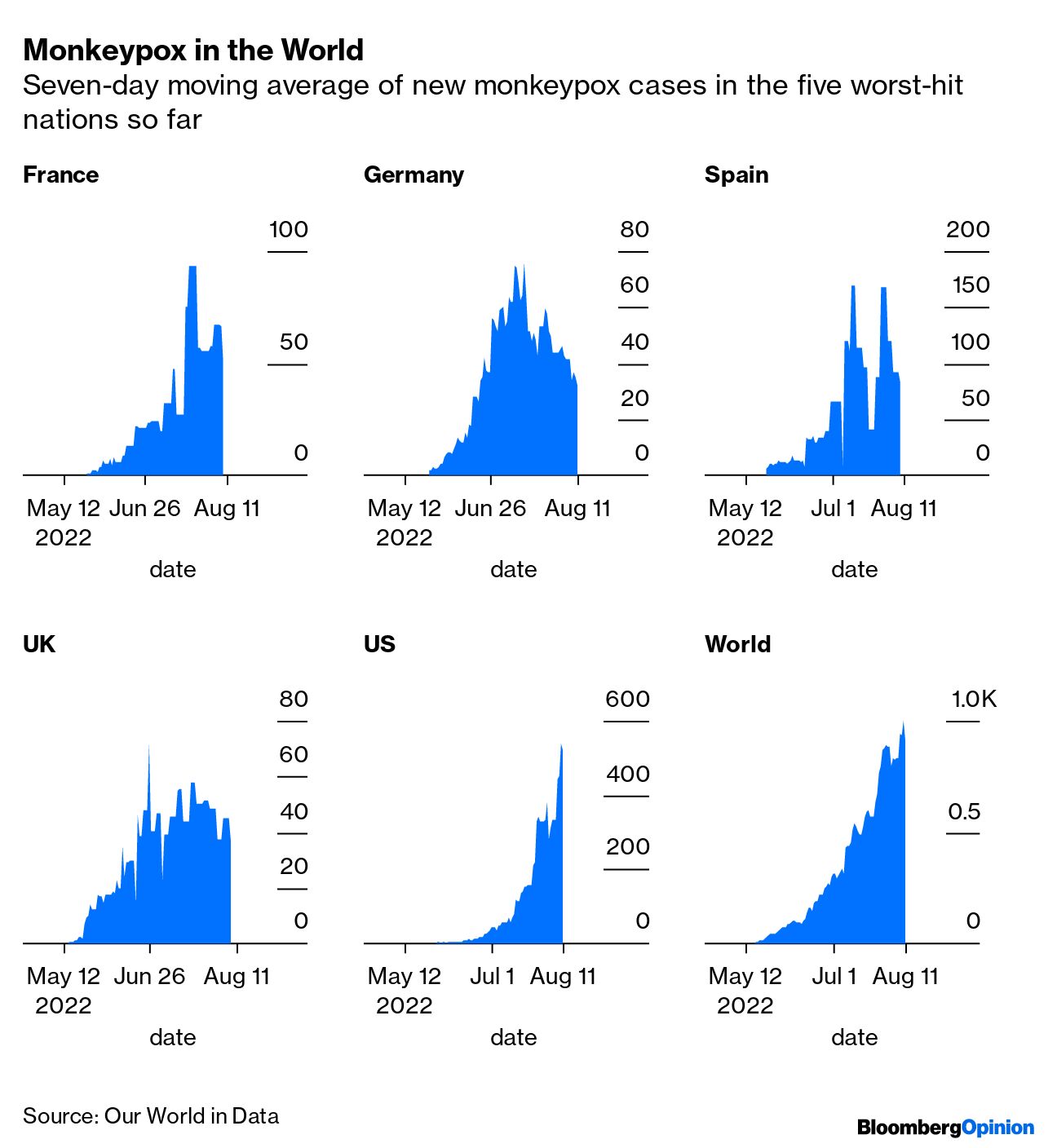

Speaking of building trust around vaccines, the US finally declared the monkeypox outbreak a public-health emergency. In theory, America has had all the right tools — tests, treatments and vaccines — to stem the spread of the disease. But access to all three has been frustratingly limited, says Lisa Jarvis.

The US’s current supply of the Jynneos vaccine — currently the best protection against monkeypox — isn’t nearly enough to cover the people most at risk. So the country has adopted a new strategy, freshly approved by the FDA. That involves administering a small dose — one-fifth of the usual size — within the skin rather than under the skin. It’ll stretch the 440,000 remaining doses into 2.2 million shots. The only problem, Lisa says, is the strategy relies on a single 2015 study. If the US is going to pursue this approach successfully, health officials are going to have to be clear about what they don’t know about the effectiveness and value of the vaccines.

Meanwhile, Covid goes on. There’s some good news in that the wave fueled by the latest variant, omicron BA.5, has finally started to ebb in the UK and parts of the US. But why? That’s a question that’ll be important as we head into winter. Faye Flam explains that viral waves are a little like a wildfire burning itself out when it runs out of fuel. Because most people retain immunity for a few weeks or months, the disease can — temporarily — run out of people to infect.

In reality, it’s a little more complicated than who’s immune and who isn’t — seasonality, population behavior and demographics are all bricks in the so-called immunity wall. Scientists are busy collecting data from wastewater and surveillance testing to get a sharper picture of why waves rise and fall, and perhaps prevent the next wave altogether.

Luckily, Covid is starting to feel like less of a threat. Wastewater studies have indicated a viral circulation as rampant as last winter’s enormous wave but with far fewer deaths and hospitalizations. The CDC is also relaxing its guidance, no longer recommending that adults and children quarantine after exposure to the virus. As life continues to feel more normal, I’ll be thanking the teams of researchers around the world watching out for the next pathogenic danger — be it a new Covid variant, the resurgence of an old disease or a brand-new virus.