peshkov

Note to readers: We recently changed the name of our service from HFI Research MLPs to HFI Research Energy Income. From the beginning, we've been focused on midstream energy equities regardless of their corporate structure, and our new name better reflects that focus. We will also be extending our coverage of energy income equities and bonds into the upstream, downstream, and oilfield services sub-sectors.

In this second part of our review of the oil bull thesis, we examine the implications of the slowdown in U.S. shale production, and we examine some of the fundamental headwinds that are holding back oil prices.

Bullish Premise #3: U.S. Shale Production Growth Is Slowing

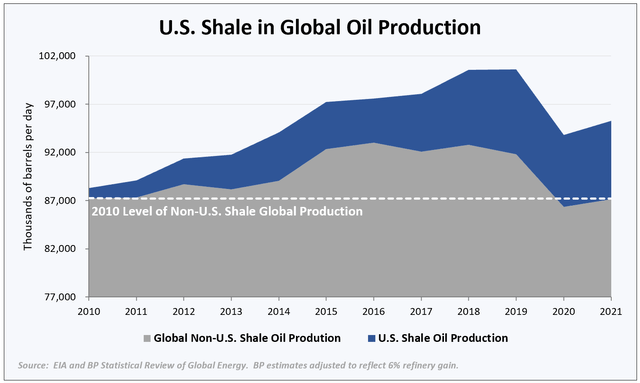

U.S. shale production has been the source of marginal oil supply since 2010. Shale has provided nearly all the net supply growth required to meet growing global demand since then. Without the explosion of U.S. shale production from 600,000 bpd in January 2010 to 8.5 million bpd today, the world would have experienced an oil supply crisis years ago. However, the shale boom didn't solve the world's oil supply problem; it simply postponed the day of reckoning.

HFI Research, EIA, BP

Shale is the most price-elastic part of the global oil supply base. Its production rate is most sensitive to shorter-term price movements. Shale can ramp production up and down in response to prices over a period of months. By contrast, non-shale production measures its reaction time in years.

In a marked change from prior years, shale has not responded to this year's higher prices with a dramatic ramp in production. Shale production is currently on pace to grow by 600,000 bpd off a base of 8.6 million bpd, which equates to an annual growth rate of 7.0%. Compare this with shale's growth rate in its 2017 heyday, when it grew by 1.4 million bpd off a base of 4.3 million bpd, for an annual growth rate of 31.5%.

The data indicate that the era of shale hyper-growth is over. The reason is partly geologic and partly economic.

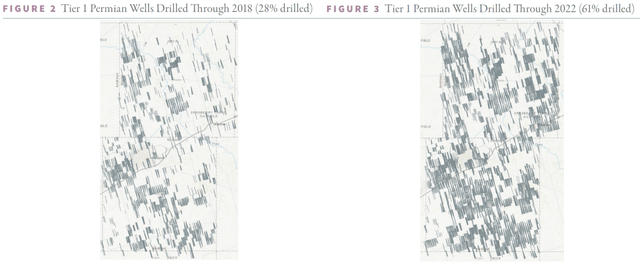

The geologic reason has to do with the limited amount of high-quality drilling locations that remain compared to previous years. The quality of a drilling location depends upon the estimated cost to drill a well and the volume of oil the well is expected to produce. The lower the cost and higher the production volume, the higher the quality. An oil producer's highest-quality drilling acreage is dubbed its "Tier 1" acreage. The Permian Basin in West Texas and Southeast New Mexico, the most prolific U.S. shale basin that produces more than half of U.S. shale oil, has several years of remaining Tier 1 drilling acreage. But it is being depleted rapidly. The maps below show that Permian Tier 1 wells were 28% depleted in 2018 but are now 61% depleted in 2022.

Goehring & Rozencwajg, “Why Won’t Oil Companies Drill?” Nov. 22, 2022, pg. 7.

As Permian production continues to grow, the number of wells that have to be drilled to grow production will increase. More wells will deplete the remaining Tier 1 inventory more rapidly.

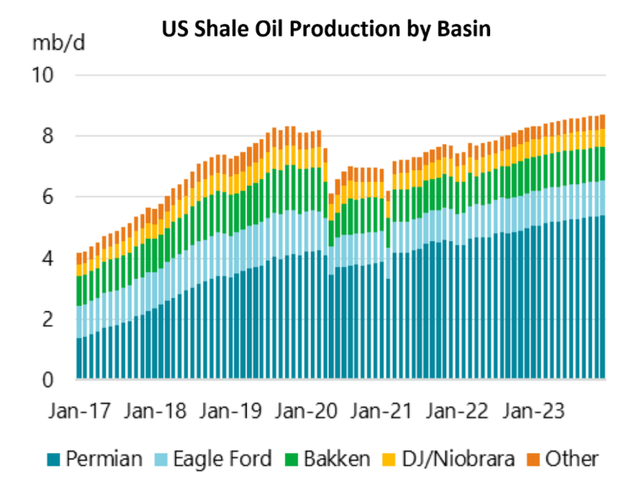

Meanwhile, the best drilling locations in the Eagle Ford and the Bakken, the second and third largest U.S. shale basins, have been largely exhausted. Production in these basins is likely to require progressively more capital to stay flat. These basins are closer to entering a long-term terminal decline, a fate to which all oilfields are subject.

In a few years, Tier 1 inventory in every shale basin will be fully depleted. At that point, producers will be forced to spend progressively more capital to drill less productive wells. This will increase the marginal cost of U.S. shale oil supply. In other words, higher oil prices will be required to elicit a supply increase.

Over the next few years, the Permian will continue to grow at a relatively high rate. However, producers are likely to manage their production so as not to blow through their remaining drilling inventory. For individual companies, less Tier 1 acreage means lower reserve volumes and a shorter life as a going concern. Companies that wish to maximize these variables will be incentivized to cut back on their inventory depletion rate. Recent consolidation among independent shale producers means that greater drilling discipline on the company level is more likely to translate to a slower pace of drilling on a basin-wide level.

The slowing overall U.S. shale production growth rate and the Permian's relatively high growth rate compared to other basins can be seen in the chart below.

International Energy Agency, Oil Market Report, Nov. 15. 2022, pg. 20.

The other cause of shale producer drilling constraint is based on economics. It reflects the failure of the old shale model of increasing production as rapidly as possible with the aim of selling to a larger firm. This model of growing production at any cost destroyed tens of billions of dollars of shareholder wealth. In recent years, however, shareholders have successfully agitated for companies to prioritize profitable production rather than production growth at any cost.

The change can be seen in corporate governance practices. Before 2020, executives were compensated based on how much production growth occurred under their watch, with little regard for the profitability of that production. It was common to see shale companies grow production at high rates only to hemorrhage cash year after year.

Today, executive compensation is aimed at maximizing free cash flow. By necessity, this requires companies to reduce capital spending to a level below the amount of cash generated by the business. This means cutting back on drilling, which leads to lower production growth. Shale companies are now comfortable growing production at a low-single-digit rate, which allows them to allocate the cash left over after drilling to paying down debt, increasing dividends, and/or repurchasing shares.

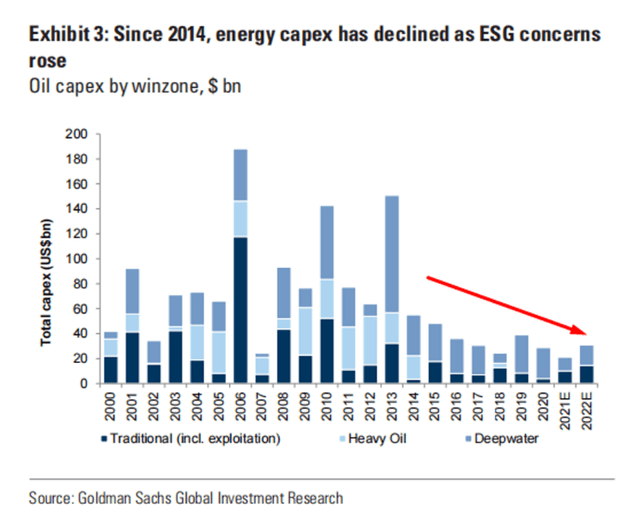

These changes in corporate governance have large-scale implications for the oil market. For years, investors mistakenly believed that U.S. shale could single-handedly meet global oil demand growth over the coming decades. Consequently, investment capital flowed into U.S. shale and away from conventional supply sources, most of which require at least five years of development before they achieve commercial production. The pullback in capital spending on conventional supply sources is pictured in the following chart.

Goldman Sachs Investment Research, Nov. 30, 2022.

The impact of the capital starvation that conventional supply sources have experienced since 2014 will become a growing problem for global supply, particularly as U.S. shale growth slows. Even when capital comes back to the industry, the long lead time required to achieve commercial production in the conventional supply base pushes back the arrival of a material supply response by at least five years.

In the future, the lack of supply growth will be a structural feature of the oil market. High prices will be necessary for years to incentivize additional production while keeping demand in check. This will be economically painful for most countries and companies, but it will be a long-term positive for oil-related equities.

The Three Bearish Factors Depressing Oil Prices

Despite oil stocks' outperformance during 2022, they continue to trade at discounts to our intrinsic value estimates. There are four causal factors at work, and each one is temporary. As they diminish over the coming months, bullish structural factors will reassert themselves.

The first bearish factor holding back oil-related equities has been large-scale SPR releases. These are set to end in a month. In addition to the U.S., as discussed in Part 1, other countries have released large quantities of oil from their SPRs throughout 2022. They include Japan, South Korea, and the larger EU nations. While the U.S. has been releasing 1 million bpd of SPR barrels, these nations have added an additional 200,000 bpd for a total supply addition of 1.2 million bpd. As these flows come to an end, they will no longer offset the supply deficit, which will continue to whittle down oil inventories to levels that prompt a surge in prices.

The second factor holding back oil prices has been remarkably stable Russian production. When Russia first invaded Ukraine, the market expected Russian production to decline by more than 1 million bpd. However, virtually no decline has materialized.

While the short-term picture has been positive for Russia, the longer-term outlook for its oil industry has deteriorated. Russia's production is sourced from aging oilfields, most of which were discovered in the 1960s and 1970s. These fields would be in terminal decline if not for the expertise and technology provided by the major international oil companies. Most of these companies exited Russia after its invasion. In the absence of the expertise and capital investment they provided, Russian production will decline, and such declines could become evident over the next year.

The third factor holding back oil prices at the moment is a rare contraction in China's oil demand. China's oil demand has increased steadily for decades. This year, however, it will decline by approximately 550,000 bpd. Since the market expected China's demand to grow by 500,000 bpd, the total demand reduction that materialized versus expectations is in excess of 1 million bpd.

The culprit behind China's weakening demand is its Covid lockdowns, which have been particularly severe in 2022. Fortunately, the strictest measures are now being relaxed. Pent-up Chinese oil demand is set to deliver a material boost to global demand throughout 2023, even if China undergoes a measured pace of reopening.

Altogether, these three bearish fundamental factors have weakened the balance between oil market supply and demand by 3.2 million bpd in 2022. As the oil market's headwinds diminish and tailwinds reassert themselves over the next few months, we believe oil prices will climb back above $100 per barrel.

Oil Prices Will be Volatile but Resilient

As long as oil prices are low enough to stimulate demand growth, oil demand is likely to be supported in virtually all economic conditions outside of major recessions and large-scale travel restrictions.

This has been the case for most of recent history. Since 1980, demand has only fallen by a significant amount twice: in the recession of the early 1980s, which reduced global GDP by 1.8%, and in the 2008-2009 recession, when global GDP contracted by 2.6%. Since the 1980s, oil demand was flat or actually increased in shallow recessions.

Meanwhile, demand in the decade before the pandemic was particularly strong. In the ten years from 2009 to 2019, global demand grew by an average of 1.4 million bpd each year. Note that this rate of oil demand growth likely exceeds OPEC's current spare capacity.

Of course, this isn't to say that prices won't fall amid bearish sentiment even when oil-market fundamentals are constructive. But fundamentals win in the end. As long as the trajectory of long-term demand amid affordable prices slopes upward, demand is likely to hold up in all but the most severe adverse economic conditions. Strong demand in a supply-constrained market should keep prices elevated.

As prices become too high for the global economy to bear, economic recessions will be necessary to force demand in line with available supply. To be sure, recessions will hurt oil demand, but a supply-constrained market is likely to be more resilient than the well-supplied oil market of the recent past. In a supply-constrained market, prices will rebound more quickly than they have in previous downturns. This is because, first, the market is likely to enter a recession with lower inventory levels. And second, when the recession arrives, OPEC will be empowered to cut production and shore up global inventories because the group won't be threatened by U.S. shale flooding the market during a price recovery. The group's proactive market management during a downturn is likely to bring about a swift oil-price recovery.

Conclusion

We present this overview of the oil bull thesis to summarize why we're committed to our oil-related equity investments. We expect high-quality oil companies operating up and down the value chain to earn higher returns on capital than their historical averages. Over time, we expect these companies' stocks to benefit from their higher free cash flow and eventually from a multiple re-rating.

In an environment characterized by high commodity prices and low capital spending, income-producing energy securities will do particularly well. We'll continue to seek conservative investments that offer substantial returns from income and capital appreciation if our thesis fails to pan out but that offer significantly more upside if it does. Given the attractive long-term outlook, income investors should take advantage of the current oil-market weakness to add high-quality names.