Stories like this further reinforce my decision to continue investing in Atlas Salt. Thanks for the shares this week as I continue to accumulate.

If history is any guide, Cargill Inc.’s sprawling salt mine underneath Cayuga Lake is likely to flood, potentially dealing a heavy blow to the Finger Lakes.

The nation’s largest private company runs the lightly-regulated, lightly-insured 8-mile-long mine, which covers several thousand acres beneath the lake owned by and leased from the state.

Pending dangers to miners working 2,300 feet underground and to the region’s invaluable drinking water source have never been fully aired. That’s because Cargill has rebuffed efforts by grassroots activists, lakeside property owners and local municipalities to shine a spotlight on them.

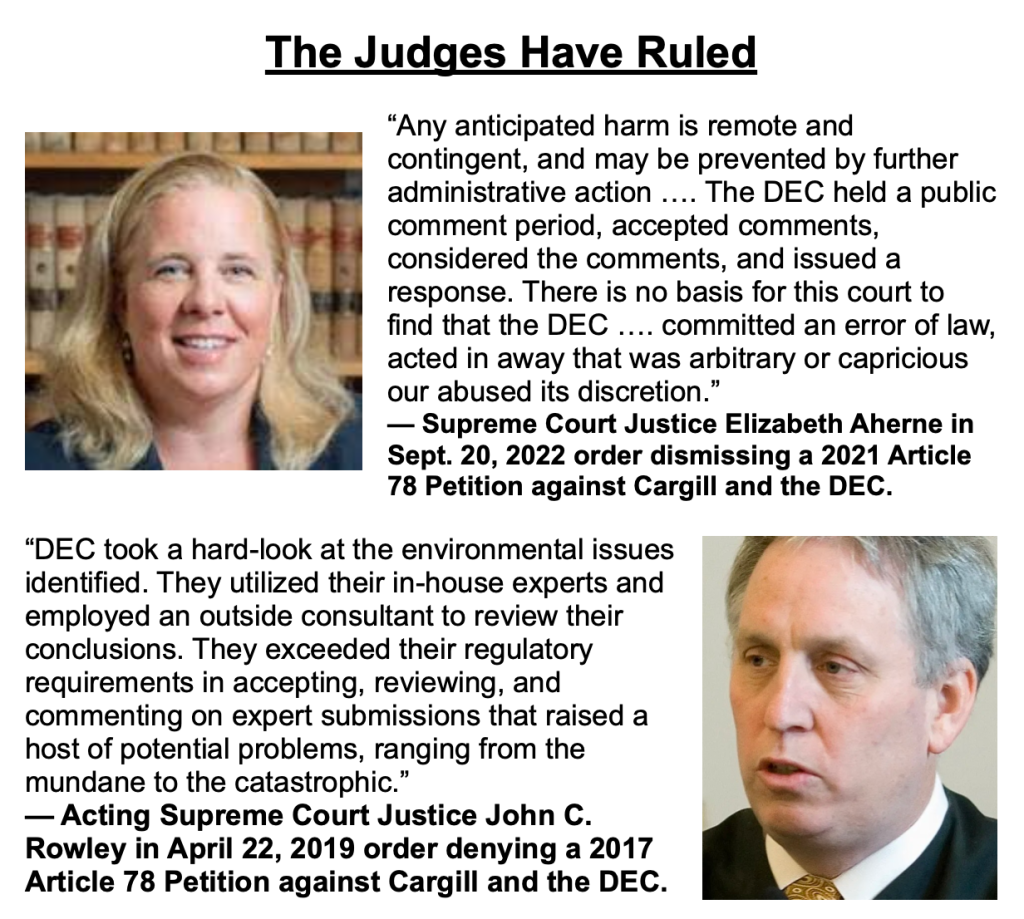

Cargill has defeated a pair of civil lawsuits that sought to force the state Department of Environmental Conservation to order a full environmental impact statement on the mine. While the landmark 1975 State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR) requires an EIS for any permitted project if there “may be one or more significant environmental impacts,” lawyers for the DEC argued those cases on the company’s side and shared in Cargill’s legal “victories.”

One of the losing plaintiffs, Louise Buck, a property owner on Cayuga’s eastern shore, voiced in an affidavit her fears that Cargill was apt to make “a mistake” while mining into rock faults or other geological “anomalies” where bedrock between the mine and the lake is relatively thin or unstable.

“This will affect my legacy to my sons and their families, and we will be the poorer for it.” said Buck, who holds a doctorate from Cornell University in natural resources management.

She expressed alarm at “the inexplicable level of risk that the DEC appears to be tolerating in the face of this industry’s activities.”

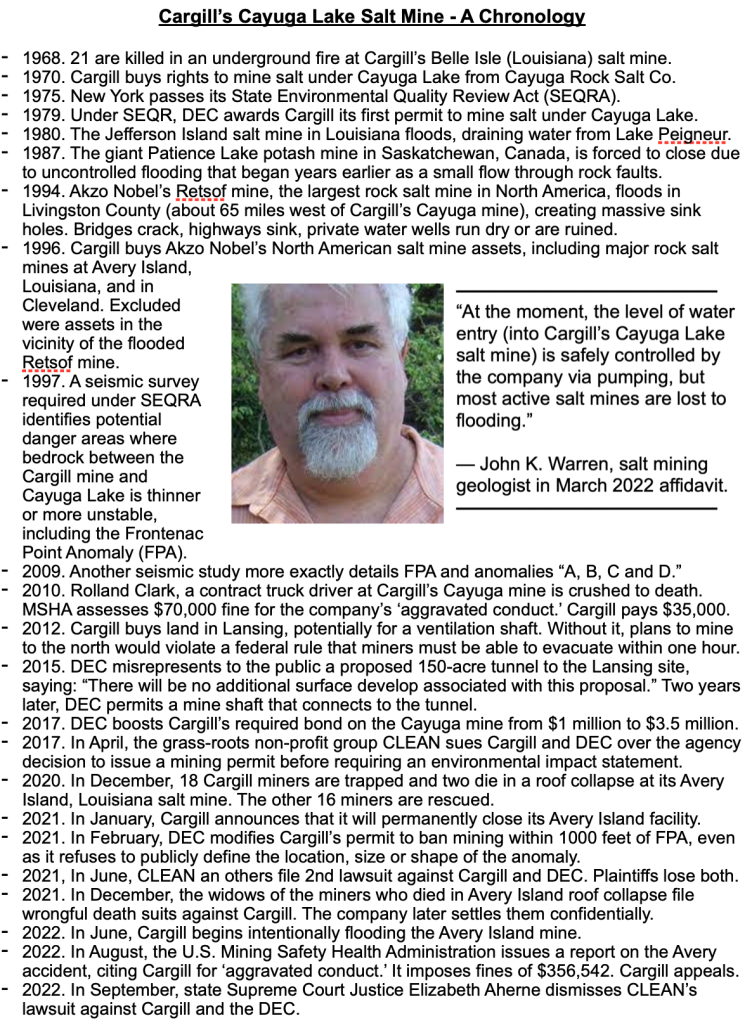

History shows that salt mining is inherently dangerous.

Two years ago, a leaking roof collapsed at Cargill’s Avery Island salt mine in Louisiana, trapping 18 miners. While 16 escaped, Lance Begnaud, 27, and Rene Romero, 41, were crushed to death.

Six weeks later the company announced that it would permanently close the mine. It began intentionally flooding it in June.

Cargill has privately settled wrongful death lawsuits filed by the widows of the two Avery Island victims.

Late this past summer, the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration assessed a $356,542 penalty, which the company is contesting. The MSHA’s final report on the fatal Dec. 14, 2020 incident concluded:

“The mine operator (a Cargill subsidiary) engaged in aggravated conduct constituting more than ordinary negligence….This violation is an unwarrantable failure to comply with a mandatory standard.”

Cargill purchased the Avery Island mine and another salt mine near Cleveland in 1996 from Akzo Nobel. The Dutch company had opted to unload its remaining North America salt mining units in the wake of the catastrophic flooding two years earlier of its Restof salt mine in Livingston County, New York.

The failure of Retsof, then the continent’s largest salt mine, caused massive sinkholes, cracked bridges and ruined water about 65 miles west of Cargill’s Cayuga mine.

The Retsof and Cayuga mines lie in similar geological formations, replete with rock folds, faults and joints that raise the risk of mining accidents.

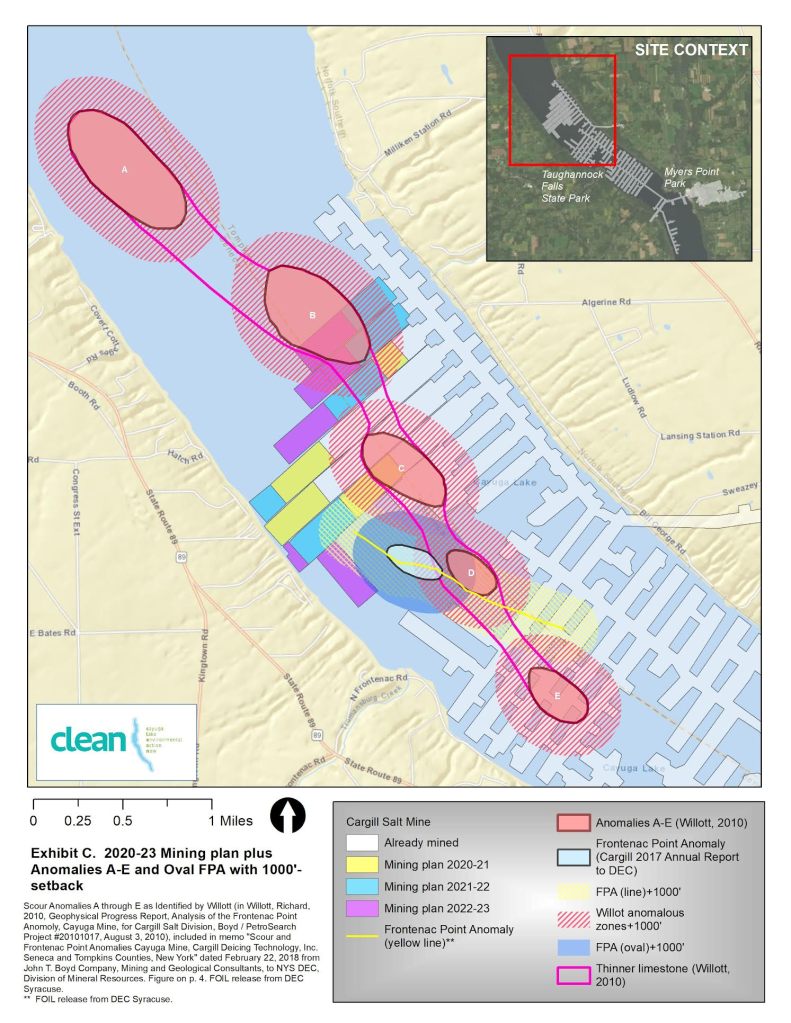

Seismic studies ordered by Cargill have identified a series of geologic “anomalies” in the path of company’s plans to mine northward.

Cargill and the DEC agree that mining under geologic anomalies may be risky. But the accepted boundaries of those zones have changed and Cargill mines under areas once deemed dangerous.

Cargill and the DEC agree that mining under geologic anomalies may be risky. But the accepted boundaries of those zones have changed and Cargill mines under areas once deemed dangerous. In February 2021, DEC announced “mostly housekeeping changes” to Cargill’s state permit that included a ban on mining within 1,000 feet of the so-called Frontenac Point Anomaly (FPA). The DEC declined a request from WaterFront to provide the FPA’s precise boundaries or to specify its location, size or shape. Instead it provided four letters from Cargill.

But the borders of anomalies have changed over the years, depending which interpretation of which study is cited.

In the case of the FPA, a 2007 map depicts it as a 7,000-foot “deep penetrating” fault, while a letter from consultant John T. Boyd Co. to DEC a decade later shows it as an oval-shaped area far less than half that long. Cargill has already mined under parts of that fault and under other sections of the mine once deemed dangerous anomalies.

An Article 78 Petition filed in 2021 by the grassroots environmental group CLEAN (Cayuga Lake Environmental Action Now) and others argued that $34 million in mined salt was riding on which version of the FPA the DEC treated as official.

(The petition was dismissed in September. A previous Article 78 Petition filed in 2017 by the City of Ithaca, CLEAN and others was denied in 2019. Both petitions were civil lawsuits that challenged DEC’s decision to grant Cargill permits without requiring an environmental impact statement.)

John Dennis, a CLEAN board member, recently asserted that the accepted borders of several anomalies have been “shrinking” over time, providing Cargill leeway to mine more freely in the future or to justify past intrusions into danger areas. He claimed that reducing the size of the anomalies could potentially free up nearly $200 million worth of mined salt.

Meanwhile, in its “housekeeping” changes to Cargill’s permit last year, the DEC ceded its express authority to hire or fire the consult the company uses (and pays for). Henceforth, the permit modification stated, Cargill alone will be responsible for “retaining … funding and managing” John T. Boyd Co. The change awarded the company power to dismiss the consultant should it produce unwelcome conclusions.

John K. Warren, an international salt mining expert hired by CLEAN, said the Frontenac Anomaly “needs protection and a protective barrier, but there is a larger issue of risks from water entry due to undocumented thinning bedrock and faulting that goes beyond the FPA….

“At the moment, the level of water entry (into the Cargill mine) is safely controlled by the company via pumping, but most active salt mines are lost to flooding,” Warren said in a 2022 affidavit.

If that applies to the Cayuga mine, what are the consequences for Cayuga Lake?

The environmental impact statement feature of SEQR, the 1975 environmental law, was written to protect communities from being blind-sided by environmental calamity. The EIS process emphasizes public involvement.

The DEC has repeatedly argued in court that an EIS is not required for the Cargill Cayuga mine. But it has twice required Cargill’s main competitor for state rock salt contracts — American Rock Salt’s Hampton Corners salt mine — to prepare one.

“Cargill seems to be worried that their mining operations under Cayuga Lake would fail to pass any EIS, whereupon DEC would be compelled to shut down the mine out of safety concerns,” Dennis said.

Shawn Wilczynski, manager of the Cayuga mine, defended Cargill’s commitment to running a safe mine in a May 2022 affidavit. He said companies like Cargill “must be able to rely on the finality of government-issued authorizations, such as permits, when making decisions about where to invest business capital.”

Wilczynski said the company responded to a permit the DEC issued in 2003 by spending more then $850 million “to develop and extract resources while protecting, implementing and refining systems to ensure the stability and sustainability of the mine and Cayuga Lake.”

The DEC has required Cargill to post a “mined land reclamation bond” payable to the agency under certain circumstances if the Cayuga mine should need to be closed.

Over the decades, the amount of that bond has gradually risen from $50,000 to $500,000, to $1 million in 1999 and finally to $3.5 million in 2017.

But that sum might not be enough to cover the costs of an unexpected mine flood, according to Richard Young, a geologist in Livingston County who has long studied the Retsof catastrophe and its messy and costly aftermath.

“Three point five million dollars seems to be a relatively small and unrealistic amount, especially without an itemized accounting or attempt to categorize the many physical and environmental issues relating to the major Finger Lakes resource,” Young said in a recent email.

An EIS process could evaluate environmental scenarios in the event of a mine flood. For example, it would analyze whether a mine flood risked raising the lake’s salinity levels to a point that it could no longer serve as a drinking water source for 40,000 people.

For property owners like Buck, an EIS could explore whether a mine flood would lower the lake’s surface level by inches or by feet and specify where sinkholes were most likely to occur.

MSHA cited Cargill for ‘aggravated conduct’ in the 2010 death of Rolland Clark, a contract truck driver for the company who was crushed to death at the Cayuga mine

MSHA cited Cargill for ‘aggravated conduct’ in the 2010 death of Rolland Clark, a contract truck driver for the company who was crushed to death at the Cayuga mine One 2017 study found that the assessed value of 2,804 Cayuga Lake water frontage properties totaled more than $1 billion. An EIS might investigate other ways a mine flood could alter the environmental character of the lake.

Cargill’s chief spokesman for North America, Daniel Sullivan, and the company’s media inquiry email contact did not respond to or acknowledge questions about the adequacy of the bond covering the Cayuga salt mine or the company’s decision to contest the MSHA fine for the fatal incident in Louisiana two years ago.

In 2010, Cargill successfully contested another assessment proposed by MSHA — for a fatal accident at the Cayuga mine. In that case, Rolland Clark, a 63-year-old contract truck driver was crushed when a 150-ton salt bin structure collapsed on his truck.

In its final report on the incident, the federal agency had concluded that the accident was caused by the overloading of a severely corroded support system.

The operator, Cargill Deicing Technology (also the operator at Avery Island in 2020), failed to properly inspect the support equipment, MSHA concluded. Its report characterized Cargill’s violation as “aggravated conduct constituting more than ordinary negligence.”

MSHA had proposed a fine of $70,000, but Cargill paid only $35,000.