The Desmarais clan is back in dealmaking mode. Only this time, it’s not simply to expand their empire — it’s to fix it.

Inside a narrow gray stone building just off Montreal’s main business district, the family and their key lieutenants are reshaping Power Corp. of Canada, the publicly traded holding company that’s the primary source of a fortune worth at least US$4.5 billion.

They’re jettisoning Putnam Investments — selling the Boston-based fund manager at a huge loss in a deal that stands to make them one of the largest outside shareholders in Franklin Templeton’s parent company. They’ve lured cash from Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund to juice growth in their private equity group, and bought a big stake in a New York wealth manager that sprung from the Rockefellers’ family office. And that’s just in the past five months.

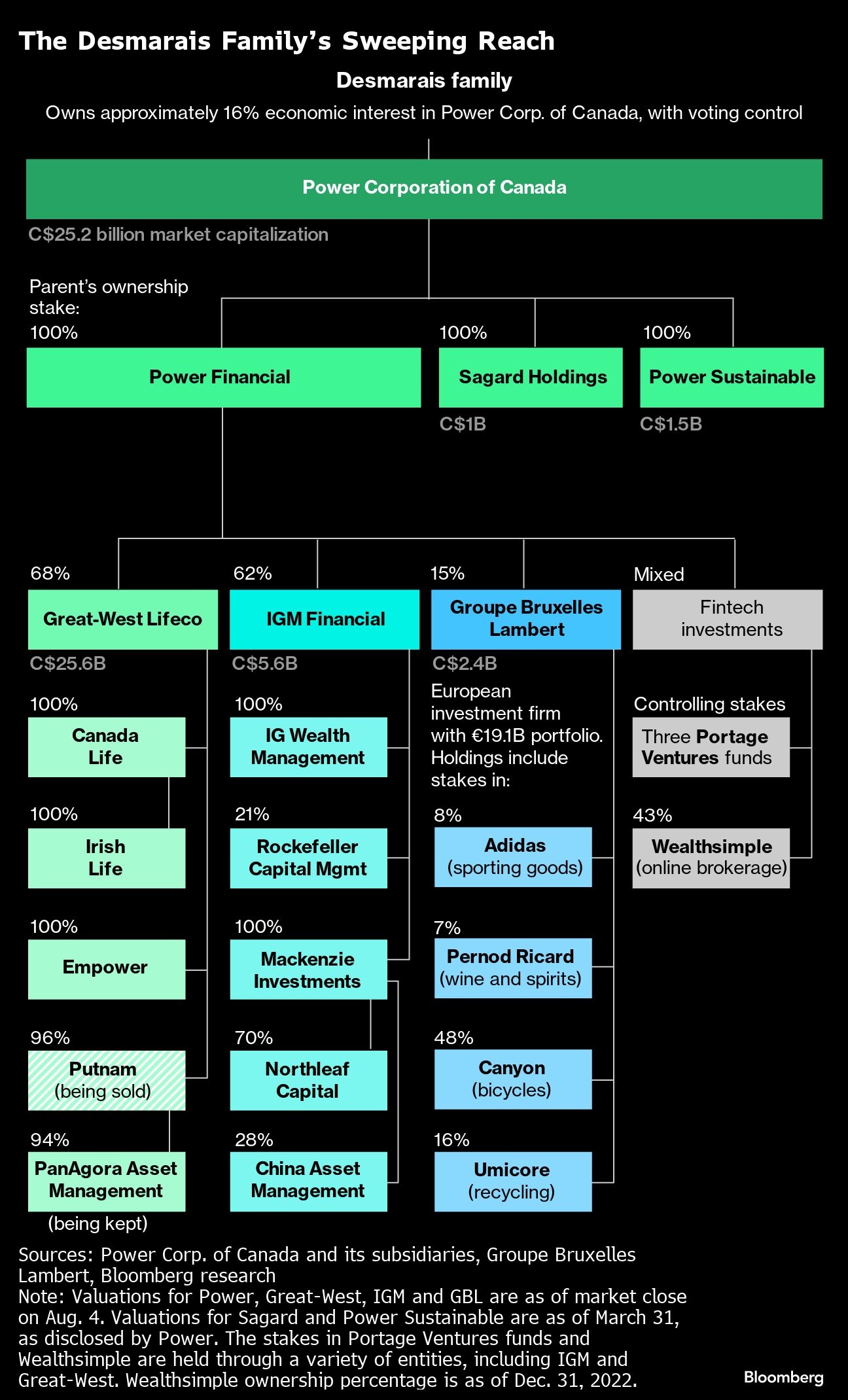

It’s all part of the most ambitious remaking of Power since the death of the patriarch, Paul Desmarais Sr., almost a decade ago. The sprawling entity, with businesses from mutual funds in China to life insurance in Ireland to 401(k) plans in the U.S., has seen its growth slow and its returns lag as it was surpassed by Brookfield Corp. as the standard-bearer in Canadian asset management. Two generations of Desmaraises, alongside an executive team led by Chief Executive Officer Jeffrey Orr, are now trying to modernize the firm, one transaction at a time.

The aim is to gain greater exposure to higher-growth areas of financial services, including managing money for Americans from the ultra-rich to the middle class, while cutting loose some legacy assets accumulated in past deals. “We were getting the message from many people that they didn’t understand what we were doing,” Orr said in an interview. “We would go out and talk to investors previously and they would say, ‘You’re too complicated.’”

An appetite for M&A has been a part of the Desmarais formula ever since Paul Sr. began his business career by taking over, and turning around, a nearly-bankrupt bus line. In the 1970s, he became one of Canada’s leading men of finance after acquiring control of Power and using it to accumulate wealth, influence, and ownership stakes in some of the country’s most coveted asset management and insurance firms.

He courted powerful friends and politicians from Beijing to Paris to Ottawa and splashed the Desmarais name on university buildings, foundations and one of Canada’s finest art galleries. When Paul Sr. died, his funeral was attended by former French President Nicolas Sarkozy and four Canadian prime ministers.

His sons, Paul Desmarais Jr. and Andre Desmarais, ran the company as co-CEOs for almost 25 years and pulled off a series of major deals of their own, while keeping a close grip on a control of the firm — via a special class of shares — and cultivating a royal mystique, rarely speaking in public.

Orr, 64, has been in the family’s orbit for decades and took over the CEO role in February 2020, becoming the first non-Desmarais in 50 years to lead Power. All signs pointed to this being an interregnum before the inevitable handover to another line of Desmarais men. Orr himself, speaking in a corporate video in 2019 said: “Everything I see is that we’re going to do the same thing into the third generation.” The career development of Paul Desmarais III and Olivier Desmarais, cousins who are now 41 years old, “is not being left to chance.”

Investors and analysts can’t help but speculate whether, or when, a Desmarais will occupy the top job again. CEO succession is “a decision for the future” because Orr doesn’t plan on retiring soon, according to General Counsel Stephane Lemay. Paul III currently runs a fast-growing fintech unit of the company, while Olivier helms a sustainability venture. However, it would be a mistake to assume that a Desmarais will be the successor, Lemay told Bloomberg.

“The Desmarais family’s current thinking is that the next generation of Desmarais would play active leadership and stewardship roles at the Power Corp. and main subsidiaries board of directors level, and not at the management level,” he said. Members of the Desmarais family declined to speak to Bloomberg for this story.

For now, it’s Orr’s job to prepare the company, which has about $2 trillion in assets under management and administration through its many divisions, for whoever comes next.

As a Bank of Montreal executive, Orr helped the Desmarais family reel in a number of acquisition targets before they persuaded him, in 2001, to join the firm. Ever since, he’s had a guiding hand in the company’s two most important businesses: IGM Financial Inc., one of Canada’s largest sellers of mutual funds and the 28 per cent owner of China Asset Management Co.; and Great-West Lifeco Inc., an insurance and benefits firm that owns Empower, the second-biggest provider of employee retirement plans in the U.S. after Fidelity Investments.

Both companies have faltered as the rise of passive investing hurt old-line asset managers offering traditional stock and bond portfolios at relatively high prices. At IGM, earnings grew an average of just 2 per cent a year over the past decade. Putnam, acquired for $3 billion in 2007 as a turnaround play after a mutual-fund scandal, went on to lose more assets. In the May deal with Franklin Templeton, Power agreed to offload most of the company for an initial $925 million, with the possibility of further payments based on results.

“We struggled financially and economically to make a profit at it,” Orr said after the deal was announced. “Putnam had a great performance, but when the market is not purchasing active funds, it did not translate into positive flows.”

Other deals have been designed to boost the firm’s exposure to trendier areas of asset management, including private equity and private credit, which have exploded in the past 15 years to total almost $10 trillion, according to financial-data provider Preqin. It’s one reason Power bought a 70 per cent stake in Toronto-based Northleaf Capital, a manager of private funds, and began offering those products to customers of IGM and Great-West.

The quest for new growth avenues guided Power to take a 20.5 per cent interest in Rockefeller Capital Management, the wealth and investment advisory firm with $105 billion in client assets that arose from the Rockefellers’ family office. “We wanted to have a presence in the wealth management business and in the high-net-worth business in a bigger way,” Orr said.

The deal, which was done through IGM, underscored that, whatever their recent challenges, the Desmarais clan still travels in the gilded of circles in finance. Andre Desmarais had a close relationship with the late David Rockefeller Sr., who acted as a mentor, according to Rockefeller Capital CEO Greg Fleming.

Rockefeller, in turn, hopes to exploit its Canadian partner’s extensive overseas connections. “Over time, we will look to build outside the U.S., and Power and the Desmaraises have a lot of history and some powerful footprints and contacts in other parts of the world, including Europe and China,” said Fleming, the former president of Morgan Stanley’s wealth-management unit.

While their global business connections endure, the Desmarais’ quiet political influence has waned, according to a number of people close to the situation.

In Paul Desmarais Sr.’s day, the family and the company used their control of media outlets – particularly La Presse, an influential Montreal newspaper — to fight surging separatist politicians in the French-speaking province.

Major policy decisions around Canada’s financial sector tended to go their way. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Canada’s largest banks made a push for mergers and liberalized rules that would make it easier for them to sell insurance through their branches. Their ambitions were mostly foiled in Ottawa, to the benefit of insurance companies such as Great-West. A freeze on mergers among Canada’s largest banks and life insurers has remained de facto government policy for more than 20 years.

But politics and media are radically different now. Quebec’s independence movement has faded; La Presse published its final print edition in 2017 and the family gave it up (it’s now an online publication run by a nonprofit trust).

The days of Prime Minister Jean Chretien, who’s Andre Desmarais’ father-in-law, and Paul Martin, a former Power executive who succeeded Chretien in Canada’s highest political office, are long gone. Justin Trudeau’s government isn’t as tight with the business community.

You can still find Power people inside organizations that try to shape the policy agenda: Olivier Desmarais, for example, is chair of the Canada China Business Council, a group that Power helped launch in the 1970s to forge closer commercial ties between the two nations. But it seems unlikely the company will be able to do any significant new ventures in China, given the countries’ fractious relationship.

FINTECH BETS

The pace of Power’s recent dealmaking is reminiscent of Paul Sr.’s early days. But there’s still a long way to go before investors will be fully convinced of the strategy. Power’s share price trades at about a 25 per cent discount to the net asset value of what it owns, according to Barclays analyst John Aiken. A discount isn’t uncommon for complex holding companies, and reducing it is something of an obsession inside Power.

“They’ve done a fair amount of work to try to unlock value, and the market is not giving them full credit for it,” Aiken said, though the discount has narrowed somewhat in recent years.

Of greater long-term consequence, perhaps, is whether Power will be able to build a profitable new line of business in managing private equity, venture capital and credit funds. It’s here that the third generation of the Desmarais family is trying to make its mark.

Paul Desmarais III, who spent five years at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. after graduating from Harvard University, was given the reins of Sagard Holdings in 2016 with a mandate to expand it globally. It’s been a mixed success with the collapse of private tech company valuations in 2022 and the scarcity of third-party capital.

Sagard puts a heavy emphasis on financial technology companies, a strategy that led Power into a major victory when it funded and acquired control of Wealthsimple Financial Corp., an online investment service that was briefly valued at $4 billion two years ago. Sagard is into everything from money transfer apps in Mexico, to online insurance sales in France, to investing apps for young Australians.

“We like finding sectors that are niche and where sector expertise matters,” Paul III said on a podcast last year. In the financial sector, “we have a real right to win, as long as we build the expertise and we build the networks that are required to win.”

Those networks may need to include rich investors from the Middle East and Asia, if Sagard is to have any hope of playing against global alternative-asset managers. Within Sagard and its sister company, Power Sustainable — which is run by Olivier — there’s less than $15 billion of outside capital as of March. Within Power itself, that’s a rounding error, and both firms run at a small loss.

In July, Bank of Montreal and the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund ADQ bought minority equity stakes in Sagard and committed, along with Great-West, to invest about $2 billion collectively in its funds, according to a person familiar with the details of the transaction.

Sagard’s emphasis on financial technology is also kind of a hedge for the parent. If you’re going to run a lumbering insurance giant, you might want to own some startups that would otherwise try to disrupt your business, or have interesting technology you can use.

“It’s an adventure in fintech,” Paul Desmarais III once said, because “we have no idea where it’s going to end.” The clash with the old world of Canadian finance, once ruled by his grandfather, couldn’t be more apparent.

With assistance from Devon Pendleton.