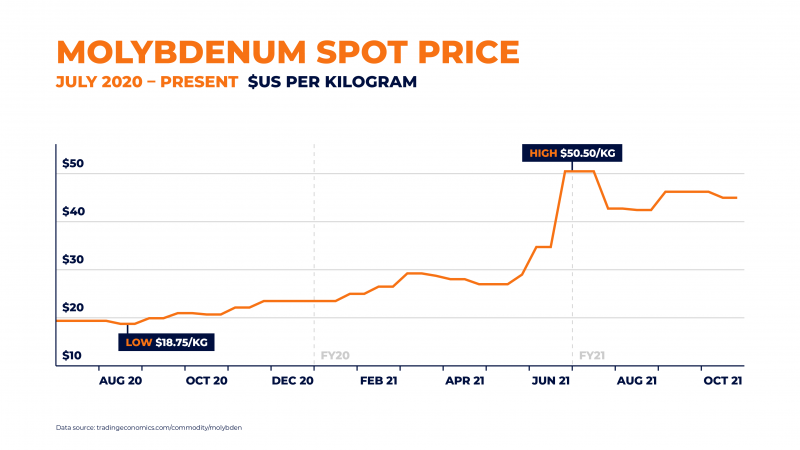

- Molybdenum has had a remarkable recent price run, rising from under US$20 (A$26.62) per kg in July 2020 to around US$45 (A$60) per kg in October 2021

- Mined mostly as a by-product of other metals and used mostly as an alloy, it’s molybdenum’s close links to steel that have helped drive this price increase

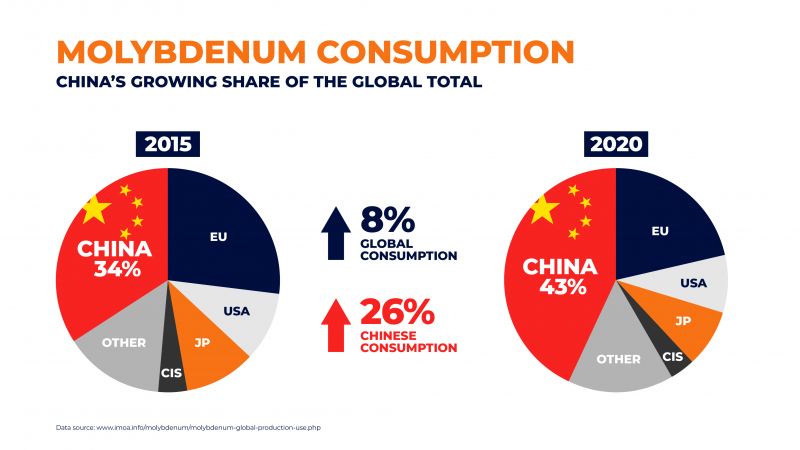

- China has been buying up huge amounts of molybdenum over the past 12 months as it turns to infrastructure to support its COVID-19 recovery

- Further, demand for molybdenum is being supported by the metal’s applications in energy creation, defence products, and new applications powering electric vehicles

- For investors, this means now could be a crucial time to get on top of the trend before global markets wake up to the future of the molybdenum market

The past 12 months have seen soaring commodity prices in global markets.

Yet, while lithium, gold, and iron ore have hogged the spotlight, one hard-to-pronounce material has been quietly but steadily increasing in value: molybdenum.

Often shortened to ‘moly’, molybdenum is not well known nor widely traded, but its spot price has risen from just under US$20 (A$26.62) per kilogram in July 2020 to around US$45 (A$60) per kilogram in October 2021.

Data sourced London Metals Exchange (LME)

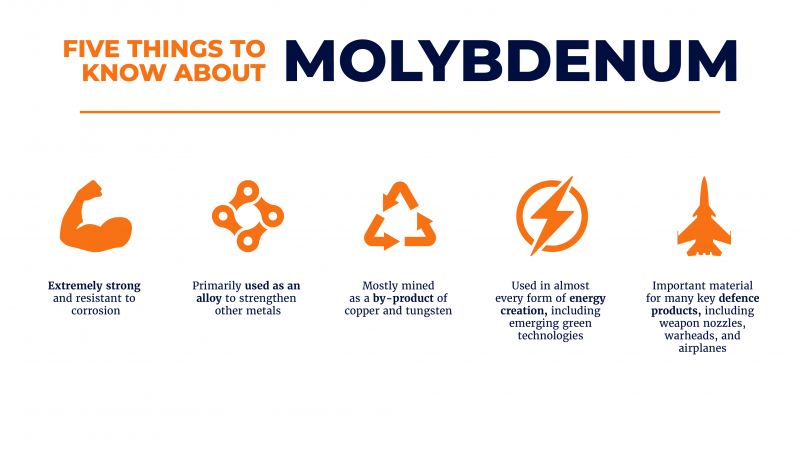

Data sourced London Metals Exchange (LME) Interestingly, moly is rarely mined on its own. Rather, the metal is often produced as a by-product of other mining operations such as copper, tungsten, and iron ore.

It’s moly’s close ties to steel, then, that has caused the price surge.

The key uses of molybdenum

Molybdenum is rarely used by itself. At a human level, the metal can be toxic in large amounts. Yet, it’s needed as a cofactor to absorb a variety of enzymes.

At an industrial level, moly can withstand extremely high temperatures without softening and has powerful anti-corrosive properties — meaning it can be used to make important alloys.

In steel, for example, moly can increase strength, hardness, resistance to corrosion, and electrical conductivity.

When chromium is added to the mix, these advantages are only improved.

It’s no surprise, then, that moly-steel alloys have important uses in the industrial and construction sectors, as well as a wide range of applications in products such as engines, air conditioners, and drill heads.

The strength of the metal also makes it crucial in military equipment and defence products.

Why the price increase?

There are three main reasons for the recent molybdenum price hike:

- China has been buying up huge amounts of the metal over the past 12 months.

- Researchers have begun to look to molybdenum as a core element for the future of lithium-based batteries and electric vehicles.

- Rising geopolitical tensions are putting pressure on nations around the world to invest more into their defence sectors where molybdenum has important applications.

Of course, this is not to mention the subdued molybdenum prices over 2020 caused by an oversupply of the material.

When the pandemic struck and lockdowns were introduced around the world, construction and steelmaking were largely put on hold.

A 2021 report from international commodity market researcher Roskill found that roughly two-thirds of molybdenum mine production takes the form of by-product operations — meaning the supply of the metal is not dependent on the moly market’s needs.

As such, though demand for molybdenum was low, its supply remained steady, and its price dropped.

Until 2021, that is.

The Roskill report said while steel and stainless steel production, combined with renewed drilling activity in the oil sector, are partly responsible for the recent moly price rise, it seems China is driving the growth.

China soaking up the world’s molybdenum supply

While moly has largely gone unnoticed for the past year, China — already the world’s largest molybdenum producer — began importing mass amounts of the metal halfway through 2021, sending the moly price through the roof.

Speculation suggests that as China cuts steel production amid plans to pursue a target of net-zero carbon emission by 2060, it is focussing on producing larger amounts of high-quality steel and curbing the production of weak or defective steel.

This is where molybdenum comes in.

If China can enhance the steel it produces, it may not need to produce as much steel to keep up with its infrastructure needs — hence its growing stockpile of moly.

The unsung hero of green energy?

Speaking of carbon neutrality, molybdenum has also been hailed by some researchers as the future of the lithium-based battery industry.

Researchers at the University of Texas found in 2018 that lithium-sulphur batteries have potential advantages in the electric vehicle industry over lithium-ion batteries, including increased energy storage, cheaper production, and safer use.

However, the tech does not yet exist to produce stable lithium-sulphur batteries. Moly, with its strengthening properties, may offer a potential solution.

Moly already has important applications in almost every form of energy creation — including the new age of solar panels and hydrogen power plants.

What’s more, a 2018 article published in the Resources Conservation and Recycling journal found that there was “little to no substitution potential” for molybdenum in its major energy applications.

Geopolitical pressure

For all its uses in the energy world, molybdenum’s strength makes it an important part of many materials in the defence sector, where the ability to withstand big hits and high temperatures is crucial.

The metal is used in a range of military applications including planes, warheads, shaped charge liners, weapon nozzles, and rotor blades.

This means further to moly’s use in energy and steelmaking, the demand for the metal may be bolstered by rising geopolitical tensions causing nations around the world to strengthen their armed forces.

With China buying up moly supply, the potential of the metal to help power lithium-sulphur batteries, and molybdenum’s existing applications in energy and defence, India-based Mordor Intelligence predicts that moly prices will continue to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 4 per cent through to 2026.

Why does this matter for ASX investors?

The takeaway for investors is this: China is stockpiling molybdenum because it realises the importance of the metal.

For investors, the best exposure to a thinly-traded metal like moly is often through companies that are producing the material rather than through trading the material itself.

This means now could be a crucial time to get on top of the trend before global markets wake up to the future of the molybdenum market.