While the on-again-off-again US-China trade war has taken a media attention backseat to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, vital supply chain risks and imbalances continue to dog various metals markets.

Supply chain imbalances for the rare earth elements like manganese are nothing new. Advanced democratic economies continue to be without a reliable domestic manganese supply chain, and this poses significant problems for economic growth amongst the G7 nations. Why? Because of the electric vehicle (EV) revolution, amongst other industrial applications.

Thus, mining exploration companies are scrambling for opportunities to fill supply chain gaps for ultra-high purity manganese products utilized in the lithium-ion battery industry.

In 2019, China unofficially floated the threat of cutting off rare earths exports to the US. The elements are largely unknown to most but are present in nearly every high-tech gadget we rely upon, from smart phones to laptops as well as electric vehicle engines, wind turbines, LEDs and, not incidentally, all major modern weapons systems. These are all key to advanced economy’s manufacturing sector.

An oft-referenced figure is that China now produces some 95 percent of the world’s rare earths, but

Eugene Gholz, a rare earth expert and associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, says this statistic is “wildly out of date.” The United States Geological Survey (USGS)

pegs China’s component as closer to 80 percent. The mere mention that China might use rare earths access as an economic weapon sent shivers through the financial markets.

China’s

stranglehold of the rare earths market is a fairly recent state of affairs. Between the 1960s and the 1980s, the majority of the world’s supply was produced in US from the giant

Mountain Pass mine in California. The mine’s processing plant was shut down in 1998 after problems disposing of toxic wastewater, and the entire site was mothballed in 2002.

Whether or not China uses this leverage is a vivid reminder of the dangerous dependency that results when a nation like the US are so massively import-dependent on a critical manufacturing material. And, in fact, the danger is far worse because when it comes to North American minerals dependency, it’s not just the rare earths.

In 2018, the US Government

published a Critical Minerals List with 35 minerals and metals considered critical to the “national economy and national security” – the rare earths collectively counted as two of the 35. For 14 of the 35,

the US is 100 percent import-dependent, and in 10 of those 14 cases, China is the US’s largest supplier or the world’s largest producer. Many investors won’t remember the names of these elements from Chemistry 101, but they’re the materials base of our modern economies…used in everything from semi-conductors and super-alloys, aerospace& defense, medical equipment, LED lighting and optics, to EV batteries and fuel cells, solar cells, wind turbines, high-temperature ceramics, and steel production.

In short, these metals and minerals are the ignition starters of our technology-based economies.

Getting to Know Manganese Ore and Manganese Products

Today, manganese ore is still primarily used in the iron and steel industry and serves as an important metal mineral in national economies. It is difficult to substantially increase the output of China’s manganese ore as a result of its low-grade and high-impurity content. However, as a large consumer in the world, it is very important to ensure the long-term stable supply of this mineral.

By collecting historical data on manganese ore in China over the past 20 years, minerals analysts have identified and assessed the risks during the whole process of production, supply, consumption, reserves, and trade of resources by selecting nine indicators –

- current market equilibrium

- market price volatility

- reserve / production ratio

- import dependence

- import concentration

- nation risks

- nation concentration

- and, future supply and demand trend.

Furthermore, its economic importance is calculated by the contribution of manganese ore engaged in different value chains. It shows the same downward trend both in manganese ore consumption and economic importance, and the future demand of manganese ore will slow down, and the global supply will exceed demand.

Based on the wide-ranging evaluation of supply and demand trends in the past and future, it was determined that the current market balance, import dependence, and country concentration risks are the chief driving factors for the supply risk of manganese ore in China, showing higher supply risk than other factors.

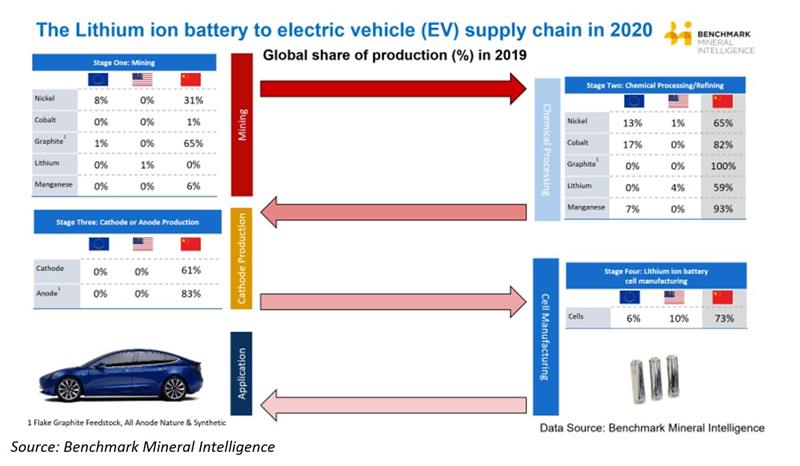

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

In each case, failure to produce sufficient supply raises the risk of unexpected supply chain disruption – think acts of nature, or labor strikes, or coups and civil strife – or the deliberate use of withholding metals access as an economic weapon or in time of conflict, as in the current case of the rare earths.

As a result, the US, Canada, and other industrial democracies have got to mine more of these materials, like manganese, and also recycle and recover them from sources that up until now have been ending up in the scrap yards.

For example, lithium-ion batteries from the first-generation EVs are now being traded in used car lots. The vehicles may be scrap, but the batteries in them are brimming with lithium cobalt, nickel, and, of course, manganese. These metals were in ultra-pure form when they went into the new battery.

Enter companies like

American Manganese Inc.

(AMY) (

TSX-V.AMY) that has developed a patented process to extract these materials and restore them to that original purity for re-use in next-gen batteries, or other technology applications. The more of this we do, the less likely it will be that another nation will hold the US or Canada hostage to critical metals supply.

AMY makes its way by pursuing innovation in the resource recycling space. What about incentivizing innovation in undervalued capital markets we need to fund our innovators?

In Canada, we have a tool that works quite well. It’s called

flow-through financing and the model – unlike so much of modern tax codes – is simple:

the dollar-value of an investment into a resource developing company can be deducted by the investor from capital gains. Resultingly, the receiving company surrenders its right to expense that dollar amount which then “flows-through” to the investor. The company secures the capital and the investor acquires the tax benefit. And society gets the metals and minerals that are essential to modern, functioning economies.

Another company involved in the recycling sector is

Euro Manganese Inc. (ENM) (

TSX-V.EMN,

Forum) – a Canadian public company focused exclusively on the development of a new high-purity manganese production facility, based on the recycling of a tailings deposit strategically situated in the heart of Europe.

The company owns Western Europe’s largest manganese deposit, located in the Czech Republic, amidst a major emerging cluster of EV, cathode, and battery plants. EMN says its goal is to become

the preferred supplier of sustainably-produced ultra-high-purity manganese products for the lithium-ion battery industry and for producers of specialty steel, high-technology chemicals/ and aluminum alloys.

Chvaletice Manganese tailings, Czech Republic: Excellent infrastructure. Next to power plant, rail line, highway, and gas line. (Photo courtesy Euro Manganese Inc.)

In Conclusion

Chvaletice Manganese tailings, Czech Republic: Excellent infrastructure. Next to power plant, rail line, highway, and gas line. (Photo courtesy Euro Manganese Inc.)

In Conclusion

The rare earth fight is a wake-up call. Tech-centric economies like the US, Canada, and their industrial democratic allies are going to need a stable supply of tech metals and minerals, like manganese, that are essential to our innovation-based economies. It’s times like these that economies must get equally innovative about how to encourage capital investment to supply these minerals to the manufacturers who depend upon them.

FULL DISCLOSURE: Euro Manganese is a client of Stockhouse Publishing.