Vanadium, the extremely hard yet ductile and malleable silvery-grey metal was named after Vanadis, the Scandinavian goddess of beauty.

The beauty of vanadium for investors is that the fundamental factors affecting demand and supply have changed significantly over the last few years. Global demand is strong and growing while supply is tight.

Vanadium supply is coming mainly from China, Russia, South Africa and Brazil. With recent mine shutdowns in China and South Africa, along with China’s ban on scrap imports, the supply side appears weak in light of the excess demand that is building up globally.

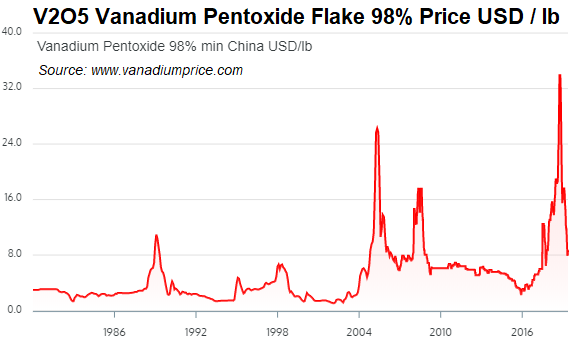

Both supply and demand pressures pushed vanadium prices from about $5 USD/lb in 2016 to more than $30 USD/lb last year. The first half of 2019 saw vanadium prices decline to $8 USD/lb, but with supply-demand fundamentals looking all the more strong, the second half of 2019 could bring a price rebound with vanadium stocks soaring again.

Source

The United States imports more than 90% of the vanadium they need for steel strengthening and utility-scale battery storage technology. As such, the US has classified vanadium as a critical metal for its economic and national security. New domestic vanadium supply is needed to offset the nation’s problematic dependency on imports from countries such as China and Russia.

In April 2019, Pistol Bay Mining Inc. (TSX.V: PST) signed an agreement to acquire a vanadium project in Nevada, USA. The 980 acres (397 hectares) land package is located in Clark County, a historical mining district with 34 reported occurrences of vanadium mineralization. With a current market capitalization of $2.3 million CAD, Pistol Bay aims to create significant shareholder value by advancing the prospect of a new vanadium district in Nevada. Pistol Bay’s President and CEO, Charles Desjardins, explained the reasoning behind signing an agreement to acquire the Vanadium Claims Group (VCG) Project in Nevada:

“We are excited to make this acquisition as it provides the Company exposure to the District Scale Potential of the area for high grade Vanadium mineralization, low cost exploration as well as potential for significant by-product credits (lead, zinc, silver) from related mineralization in a district that [has] not been systematically explored for vanadium.”

The mining district was mapped by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in the 1920s. Most interestingly, the USGS report (“Geology and Ore Deposits of the Goodsprings Quadrangle, Nevada“ by D. F. Hewett, 1931) includes the following remark: “Vanadates of either lead, zinc, or copper are uncommonly widespread in the district, but only a few specific determinations of the minerals were made.”

According to Pistol Bay‘s news-release:

“[S]ignificant concentrations of vanadium were shipped from the district in the form of mine concentrates and bulk shipments. The USGS report also mentions a number of other references to vanadium mineralization in the district:

a) concentrates reported to contain 15% V2O5

b) 3.75% V205 over 2.3m,

c) 3m wide zone estimated to run up to 10% V2O5“

That‘s pretty high-grade vanadium!

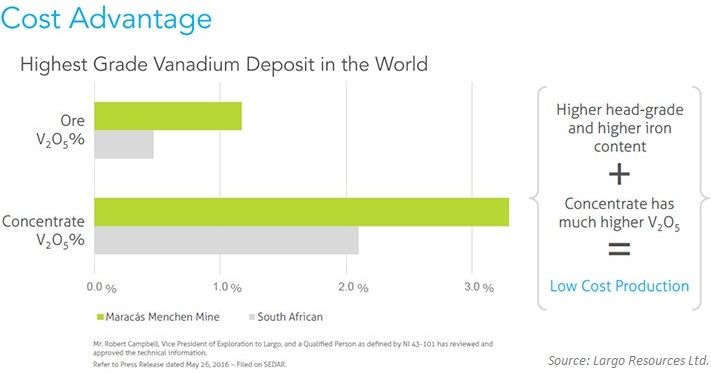

Almost 100 years after this USGS report, USGS (the sole science agency for the Department of the Interior) published a report on vanadium (“Critical Mineral Resources of the United States“) in which the location, grade, tonnage, and other data for selected vanadium deposits of the world are listed (page 14-18). The reported vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) grades range from 0.084% in Russia, 0.52% to 1.5% in South Africa, and 0.29% in Sweden. The listed deposits in the US have V2O5 grades between 0.19% (Utah), 0.51% (Nevada), 1.15% (New Mexico and Arizona), 1.29% (Colorado) and 1.46% (Utah).

In other words: Anything above 1% V2O5 is pretty high-grade!

Full size / The Maracás Menchen Mine in the state of Bahia, Brazil, is touted as the highest grade vanadium deposit in the world. (Source: Largo Resources Ltd.)

“The USGS reported that a number of outcrops from within the two areas covered by the VCG project contained vanadium mineralization and that shipments of vanadium mineralization were made from one of the areas now covered by the VCG project“, Pistol Bay stated and added: “Vanadium concentrations are reported in mine concentrates, bulk shipments and outcrops. No reference to exploration for vanadium mineralization were noted. It appears that the Goodsprings District has not been systematically explored for Vanadium mineralization.“

A systematic exploration program by Pistol Bay could locate a number of vanadium zones. As such, the exploration potential for high-grade vanadium mineralization should logically be reasonable. Clearly, with a report that is 100 years old, its value is only historic and potentially indicative at best. Even with a government branch like the USGS, the grades are not being taken at face value. But it does point to a general region where vanadium could potentially exist in commercial quantities.

Pistol Bay noted that “The USGS described the styles of mineralization within the district and recorded a significant number of vanadium occurrences containing vanadinite, descloizite, cuprodescloizite, psittacinite and other unnamed vanadium minerals“ and that globally “The most important vanadium bearing minerals are vanadinite (19% V2O5), descloizite (22% V2O5), cuprodescloizite (17-22% V2O5), carnotite (20% V2O5), roscoelite (21-29% V2O5), and patronite (17-29% V2O5)“.

Vanadium deposits may be:

• Endogenic: Characterized by a low vanadium content (0.1-1% V2O5), but the reserves are very large; or:

• Exogenic: Include descloizite, cuprodescloizite, and vanadinite deposits in oxidation zones of lead-zinc and copper ores (containing 2-10% V2O5).

Pistol Bay stated that “The vanadium mineralization exposed within the VCG project belongs to the Exogenic type vanadium deposits characterized by typically higher grade (2-10% V2O5) mineralization; the vanadium minerals descloizite, cuprodescloizite and vanadinite and occur in oxidation zones of lead-zinc and copper mineralization“ and that “Hewett reported 34 occurrences of vanadium mineralization occur throughout the District“.

The Vanadium Claims Group Project

Claims Group #1

“Measures approximately 1.6 km by 1.0 km covering a number of reported vanadium showings exposed in outcrop and in old mine workings“, Pistol Bay noted. The USGS report states: “Vanadinite and cuprodescloizite are common in the principal workings as well as in several pits near by. According to J. Doran, one of the owners, one lot of 14 tons of material was shipped in 1920 from these workings to the American Vanadium Co.” Information on the vanadium content of the shipment is not available.

Claims Group #2

“Covers an area measuring approximately 1.6 km by 1.0 km with reported vanadium mineralization and a significant number of old workings“, Pistol Bay said and added that “No exploration has been completed on the two groups“ and that “Access to the properties is excellent using dirt roads and trails. Fuel, lodging and material are available with 20 kms of the properties. The properties are within a 30minute drive from Las Vegas, Nevada“.

Moreover, Pistol Bay gave the following remarks on Claims GS 32-40:

“These claims surround the former producing Springer Mine and Tiffin Mine and are underlain by Mississippian/Pennsylvanian age Monte Cristo Limestone, Birdsprings Limestone and outliers of Miocene age andesite/latite/rhyolite flows. Late north trending mica Lamprophyres dikes cross cut the limestone units. The property covers the extension of the Sultan Thrust fault that dips to the south. The property is also host to several north-south trending west dipping faults.“

“Mineralization: The property covers an area that measures approximately 1.6 kms by 1.0 km and could be expanded to cover 3.0 kms by 2.0 kms based on host rocks and reported vanadate mineralization.“

“Past production: The Singer and Tiffin mines were former small scale lead-zinc producers (+/- 1,000 tons ore shipped, most likely hand cobbed) that operated in the 1920’s. These workings are held by patented claims and are surrounded by the GS 32-40 claim group.“

Full size

Full size

Vanadium: Strong Market Fundamentals

In late 2017, China applied new steel reinforcement standards to fight floods and earthquakes, with new regulations requiring a doubling of vanadium content in the steel used for high-rise constructions, for example.

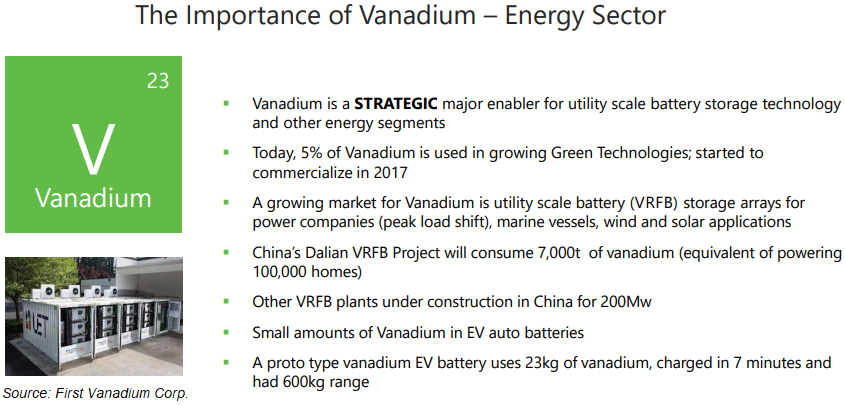

Most of global vanadium supply is used to harden steel, however the metal is also used to prevent global warming. Vanadium redox batteries are predicted to be able to recharge up to 20,000 times (although this is not yet proven), which over time could make batteries more economic than fossel fuels.

With lithium being the metal of choice for powering electric vehicles, vanadium could become its counterpart for powering stationary batteries such as large utility-scale systems to store mass energy from wind and solar parks.

At Tesla‘s shareholder meeting in June 2018, Elon Musk said that “The rate of stationary storage is going to grow exponentially. For many years to come each incremental year will be about as much as all of the preceding years, which is a crazy, crazy growth rate.“

The vanadium battery market may lack a flashy promoter like Elon Musk, but nonetheless vanadium batteries already have major backers who are betting big on its future, including Glencore, the world‘s biggest commodity trader with vanadium mines in Brazil and South Africa. And then there is Robert Friedland, the renowned billionaire and legendary mining magnate who controls VRB Energy, a fast-growing Canadian vanadium redox battery (“VRB“) technology developer and manufacturer, who proclaimed that ”Vanadium flow batteries [are] revolutionizing modern electricity grids in the way that lithium-ion batteries are enabling the global transition to electric vehicles.“

Full size

Vanadium Market Snapshot

Below excerpts sourced from Pistol Bay’s website (slightly edited):

“Vanadium is a metal that was discovered in the early 19th century. Here are some of the more common uses of vanadium in the world today!

Uses of Vanadium

• Small amounts of vanadium are added to steel to make it stronger. Surgical instruments, tools, axles, bicycle frames, crankshafts, gears and jet engines are made from this strong steel.

• Vanadium pentoxide is used as a catalyst to make sulfuric acid. Sulfuric acid is one of the most important chemicals for industry. Vanadium pentoxide is also used to make maleic anhydride and some ceramics.

• In the future, a compound of vanadium may be used in lithium batteries as an anode. It could also be used in rechargeable batteries.

• Vanadate, another compound of vanadium, protects steel from rust and corrosion.

• Vanadium dioxide is used to make glass coatings which block infrared radiation.

• Fake jewellery can be made of vanadium oxide.

• The inner structure of a nuclear fusion reactor can be used to capture neutrons making the nuclear reaction much safer.

• Superconducting magnets can be made out of vanadium.

• Some bacteria and other organisms use a vanadium compound to fix nitrogen.

• Vanadium is used for treating prediabetes and diabetes, low blood sugar, high cholesterol, heart disease, tuberculosis, syphilis, a form of “tired blood“ (anemia), and water retention (edema); for improving athletic performance in weight training; and for preventing cancer.

Back in 2006, a company decided to reopen an old vanadium mine in Nevada, electricity grids were the last thing on their minds. Back then, vanadium was all about steel. That‘s because adding in as little as 0.15% vanadium creates an exceptionally strong steel alloy. Steel mills love it. They take a bar of vanadium, throw it in the mix. At the end of the day they can keep the same strength of the metal but use 30% less. It also makes steel tools more resilient. If the name vanadium is vaguely familiar to you, it is probably because you have seen it embossed on the side of a spanner. And because vanadium steel retains its hardness at high temperatures, it is used in drill bits, circular saws, engine turbines and other moving parts that generate a lot of heat. So, steel accounts for perhaps 90% of demand for the metal.

Vanadium‘s alloying properties have been known about for well over a century. Henry Ford used it in 1908 to make the body of his Model T stronger and lighter. It was also used to make portable artillery pieces and body armour in the First World War. But vanadium‘s history seemingly goes back even further. Indeed, mankind may have been unwittingly exploiting the metal as far back as the 3rd Century BC. That is when “Damascus steel“ first began to be manufactured. Swords made of the steel were said to be so sharp that a hair would split if it were dropped on to the blade. Today, vanadium mainly goes into structural steel, such as in bridges and the “rebar“ used to reinforce concrete.

Vanadium supply is dominated by China, Russia and South Africa, where the metal is extracted mostly as a useful by-product from iron ore slag and other mining processes. China – which is midway through the longest and biggest construction boom in history – also dominates demand. A recent decision by Beijing to stop using low-quality steel rebar has bumped up forecast demand for vanadium by 40%. Yet the biggest source of future demand may have nothing to do with steel at all, and may instead exploit vanadium‘s unusual electrochemical nature.

Vanadium redox flow batteries [also called “v-flow batteries“ or "v-batteries"] are very stable. They can be discharged and recharged 20,000 times without much loss of performance and are thought to last decades (they have not been around long enough for this to have been demonstrated in practice).

Full size

Why should vanadium batteries be the technology of choice?

There is a glut of cheap lithium batteries these days, after manufacturers built out their capacity heavily in anticipation of a hybrid and electric cars boom that has yet to arrive.

Lithium batteries can deliver a lot of power very quickly, which is great if you need to balance sudden unexpected fluctuations – as may be caused by passing clouds for solar, or a passing gale for wind. But a lithium battery cannot be recharged even a tenth as many times as a vanadium battery – it‘s likely to die after 1,000 or 2,000 recharges.

Lithium batteries cannot scale up to the size needed to store an entire community‘s energy for several hours. By contrast, vanadium batteries can be made to store more energy simply by adding bigger tanks of electrolyte. They can then release it at a sedate pace as needed, unlike conventional batteries, where greater storage generally means greater power.

At the other end of the scale, there are also plenty of large-scale energy storage systems under development, such as those exploiting liquefied air, and the 1,000-fold shrinkage in the volume of the air when it is cooled to -200C. But these systems take up a lot of space and are better suited to the very largest-scale facilities that will be needed to serve for instance a large offshore wind farm plugging into the high-voltage national grid.

Source

The second really big question for vanadium is whether the world contains enough of the stuff

The immediate challenge is that the birth of the vanadium battery business is coming just as China is ramping up its demand for vanadium steel. There is also a longer-term problem – the quantities of vanadium added to steel alloys are so tiny that it is not economic to recover it from the steel at the end of its life. So for the battery market, that vanadium is effectively lost forever.

Some vanadium battery-makers have initiated development of new methods to produce vanadium electrolyte.

One of the world’s least known metals is also of great importance, and likely to become more so as renewable energies catch up with and possibly eclipse fossil fuels. Yet vanadium’s primary use as a steel alloy is set to keep prices buoyant and North American explorers racing to find a domestic source of the metal that was once used to make swords so strong and sharp the mere sight of them struck fear into the hearts of their enemies.

Twenty years ago, no vanadium went into cars, versus around 45 percent of cars today. By 2025, it’s estimated that 85 percent of all automobiles will incorporate vanadium alloy to reduce their weight, thereby increasing their fuel efficiency to conform to stringent fuel economy standards set by the US EPA.

Vanadium’s corrosion-resistant properties make it ideal for tubes and pipes manufactured to carry chemicals. Vanadium-titanium alloys have the best strength-to-weight ratio of any engineered material on earth. Less than one percent of vanadium and as little chromium makes steel shock and vibration resistant. A thin layer of vanadium is used to bond titanium to steel, making it ideal for aerospace applications. Mixing titanium with vanadium and iron strengthens and adds durability to turbines that spin up to 70,000 rpm.

Since vanadium does not easily absorb neutrons it has important applications in nuclear power. Vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) permanently fixes dyes to fabrics. Vanadium oxide is utilized as a pigment for ceramics and glass, as a chemical catalyst, and to produce superconducting magnets.

Of course, the latest application for vanadium is for batteries, particularly vanadium redox flow batteries used for grid energy storage, of which vanadium pentoxide is the main ingredient.

Full size

Where it‘s found and how it‘s mined

Vanadium is typically found within magnetite iron ore deposits and is usually mined as a by-product and not as a primary mineral. Vanadium is often agglomerated with titanium, which must be separated out as an impurity during processing. The higher the titanium content in the ore, the harder it is to remove the vanadium. The end-product is vanadium pentoxide, which can be used for the applications cited above or to make ferrovanadium for use in steel.

While V2O5 currently sells for between US$16,000 and US$17,000 a ton, titanium goes for just $US1,500 a ton, which means a low grade of titanium is an attractive feature of a vanadium prospect. Some of the world‘s key vanadium mines include the Bushveld complex in South Africa – responsible for about a quarter of all vanadium supply; the high-grade Maracas mine in Brazil owned by Largo Resources; and EVRAZ’s Vanady Tula mine in Russia, the largest European producer of vanadium pentoxide and ferrovanadium alloys.

Full size

Cities and roads girded with steel

The world needs more steel, ergo, more vanadium. The latest estimate is that vanadium demand and supply currently intersect at about 80,000 tonnes per year. Market research firm Roskill predicts that by 2020 there will be about a 45 percent increase in the demand for vanadium, driven mostly by China.

As an example of how much steel will be required to build just one new Chinese city – Xiong‘an, consider that the city will likely need 20 to 30 million tonnes of steel, which translates to 30,000 tonnes of vanadium – roughly a third of current annual production, albeit over 10 years. That means 3,000 additional tonnes of vanadium a year for the next decade, for just one city – an increase of 5 percent above current supply and demand.

Another thing going for vanadium is China‘s reluctance to manufacture low-quality rebar used in building construction. Recent earthquakes in China and Japan have shown the Chinese that using cheap rebar is penny wise and pound foolish.

China’s scrap ban will cut 4,500-5,500 tpy of domestic V2O5 production.

Chinese infrastructure investments in the New Silk Road – a $900-billion project set to open up land and maritime routes between China and its western neighbors, namely Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe – is another massive spend on steel that will likely require more vanadium than is currently being mined.

Then there are the new infrastructure demands in the United States that President Donald Trump campaigned on in 2016 and is promising to address. The state of disrepair of much of America‘s infrastructure is truly staggering. It‘s estimated that 80,000 bridges, or over half the entire stock of U.S. bridge structures, need to be repaired or replaced. Whether or not Trump‘s infrastructure bill is passed, there will certainly be a future need for more U.S. steel, and more vanadium.

Insecurity of supply

With vanadium demand expected to increase, it is a valid question as to where new vanadium supply will come from. There are currently no North American reserves, a situation that is and should be deeply alarming to politicians on both sides of the 49th parallel.

A critical or strategic metal is defined as one whose lack of availability during a national emergency would affect the economic and defensive capabilities of that country. The United States and Canada are completely dependent on recycling and imports for 100% of their vanadium supply.

Consider what happened to the rare earths market in the 2000s, when China, which produces 90 percent of REEs, restricted exports, causing prices to spike around the world. Rare earths are used in everything from cell phones to wind turbines to missile guidance systems. With just three countries – South Africa, China and Russia – controlling the supply of vanadium, there is a high risk of that supply either being cut off due to a political or trade conflict, or for the price to suddenly jump.

Conclusion

While v-flow batteries have tremendous appeal for harnessing the power of the wind and sun, their mass adoption to their direct application to the supply-demand equation for vanadium is probably a few years off. New technologies take a long time to be proven out, tested and adopted by the mainstream.

And that’s probably just as well, because vanadium suppliers likely won’t be able to keep up with the amount of demand that is coming down the pipe for the 22nd most abundant element. Think back to that single Chinese city being built – over a third of the world’s vanadium production over the next decade going into one city. That isn’t counting the expected increase in vanadium needed for steel production, defense, automobiles, aerospace, rebar and all the other vanadium applications.

The answer is to bring new vanadium mines online – especially North American deposits that can produce vanadium pentoxide and ferrovanadium, thus bringing the supply-demand curve down to a point where the price is attractive for both vanadium producers and consumers, while increasing security of supply in an increasingly hostile world.

Because vanadium is a metal that seems destined for a supply crunch, because of its applications for traditional industries like autos, aerospace, defense and steelmaking, and due to its promising potential for long-term battery storage of grid-scale electricity, companies that are developing vanadium deposits in North America need to be on your radar screen.“

Bottom Line

Vanadium market fundamentals are very compelling. Pistol Bay has realized the window of opportunity, was able to sign an agreement and expects to acquire some of the most promising – and overlooked – vanadium prospects in the United States. Upcoming exploration programs offer potential for vanadium discoveries, not to speak of zinc, lead, copper and silver.

Company Details

Pistol Bay Mining Inc.

Suite 700 – 838 West Hastings Street

Vancouver, B.C. V6C 0A6 Canada

Phone: +1 604 369 8973 or +1 604 613 3156

Email: info@pistolbaymininginc.com

www.pistolbaymininginc.com

Shares Issued & Outstanding: 50,333,822

Chart

Canadian Symbol (TSX.V): PST

Current Price: $0.045 CAD (06/18/2019)

Market Capitalization: $2.3 Million CAD

Chart

German Symbol / WKN (Frankfurt): QS2 / A12DZH

Current Price: €0.035 EUR (06/18/2019)

Market Capitalization: €1.8 Million EUR

Disclaimer: This report contains forward-looking information or forward-looking statements (collectively "forward-looking information") within the meaning of applicable securities laws. Forward-looking information is typically identified by words such as: "believe", "expect", "anticipate", "intend", "estimate", "potentially" and similar expressions, or are those, which, by their nature, refer to future events. Rockstone Research, Pistol Bay Mining Inc. and Zimtu Capital Corp. caution investors that any forward-looking information provided herein is not a guarantee of future results or performance, and that actual results may differ materially from those in forward-looking information as a result of various factors. The reader is referred to the Pistol Bay Mining Inc.´s public filings for a more complete discussion of such risk factors and their potential effects which may be accessed through the Pistol Bay Mining Inc.´s profile on SEDAR at www.sedar.com. Please read the full disclaimer within the full research report as a PDF (here) as fundamental risks and conflicts of interest exist. The author, Stephan Bogner, currently does not hold any equity position in Pistol Bay Mining Inc., however he holds a long position in Zimtu Capital Corp., and is also being paid a monthly retainer from Zimtu Capital Corp., which company also holds a long position in Pistol Bay Mining Inc. and thus would profit from price appreciation of its stock. Pistol Bay Mining Inc. has paid Zimtu Capital Corp. to provide this report and other investor awareness services. The cover picture and the last shown picture have been obtained from Dominic Gentilcore and Krsmanovic via Shutterstock.com.